Guazi video ads on “Rap of China” used boastful language typical of the hip-hop genre

How the fairly stringent restrictions of China’s 2015 Advertising Law apply to non-traditional methods of marketing such as product placement is not always clear, but in at least one case, we have seen a Chinese court strike down an innovative form of advertising that went too far in its attempt to connect a brand to the highly popular content of a reality show.

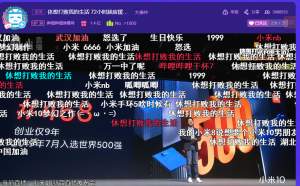

Guazi, an online used-car dealer, was one of half a dozen major sponsors on the second season of iQiyi’s breakout hit “Rap of China” (中国新说唱) in 2018. Like many other sponsors of the competition-style show, it participated in iQiyi’s innovative mid-broadcast ads that featured leading contestants on the show rapping about sponsor products with typical hip-hop swagger and bravado. These types of ads were seen as offering entertaining way of linking the content of the show (rap and hip-hop culture) with a variety of sponsor goods, ranging from mobile phones to shampoo. The rap-video ads were introduced in the first season of “Rap of China” and became more popular the following year, with nearly all top performers taking turns in a variety of increasingly elaborate ads that changed with each episode.

In one example, Guazi was featured in a roughly minute-long segment with rapper Wang Yitai singing about various sponsor products against a background of an animated Chinese ink-brush painting. Guazi’s videos included lines such as “Guazi used cars, always in the lead, excellent,” “many buyers, many sellers, always surpassing rivals,” and “industry leader, champion, and who are you?” Even though the language appears appropriate in the context of rap, China’s Advertising Law includes a strict prohibition on the use of superlatives in advertising, including terms such as “top,” “best,” “leading,” and other “extreme words.”

Rival platform Renrenche took issue with Guazi’s wording and filed a complaint in Beijing’s Chaoyang District People’s Court alleging that Guazi’s ad misled consumers and constituted unfair competition. Renrenche claimed that Guazi exaggerated its real-world position, potentially influencing unwitting customers to choose its products and services over those of others such as Renrenche. IQiyi was also named in the complaint for its role in the creation and broadcast of the ads. Renrenche sought an apology, RMB 20 million ($2.8 million) in compensation for damages, and an injunction against the use of the ads. The court, agreed, at least in part, and issued a preliminary injunction last September ordering Guazi and iQiyi to halt the ads while case proceeds.

This was not the first time Renrenche and Guazi faced off in court over advertising language. In 2017, Renrenche sued Guazi for RMB 100 million ($14.1 million) over advertising claims that it was “far ahead” of the competition, and regulators fined Guazi RMB 12.5 million ($1.8 million) for using language that “lacked a basis in facts.” Guazi also countersued Renrenche over its marketing claims of “zero down payment to buy, three days for a contract to sell.”

Given the litigious background of the competition, it could be argued that Guazi should have been especially cautious about the language it used going forward, and other brand sponsors generally have been more careful in their wording to avoid overstepping the Advertising Law’s restrictions. Nevertheless, the Guazi case highlights the risks of brand integration and shows how the courts can apply existing law to branded content, even when it arguably aims to take creative license.