Airbnb’s “Adventure Life” series merges its product offerings with “slow living” travel content

As 2019 draws to a close, it’s time to look back at some of the key ways in which brands sought to resonate with China’s consumers through entertainment and other content-driven marketing strategies. As elsewhere, growth in China’s overall advertising industry is slowing and viewer tolerance for traditional forms of advertising is declining in the new era of on-demand content, so brands have had to raise their levels of creativity to in order to have a successful impact on their target consumers. With consumption is driven by the millennial and Gen Z demographics, brands must respond with new techniques to woo these increasingly savvy and choosy buyers.

As we head into the new year, we’ll also share our predictions on the trends that will shape brand integration in 2020, so stay tuned for our outlook in the coming weeks.

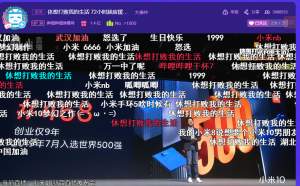

1. Livestreaming e-commerce

While livestreaming has been around for some time in China, 2019 will go down as the year that it went mainstream, with platforms, brands and celebrities all clamoring to get in on the action.

American media often compares the trend to the cable television shopping channels of an earlier era such as QVC, but a key difference is that China’s livestreaming e-commerce has developed as a mobile-first phenomenon operating across multiple platforms, with social interaction and mobile payments playing crucial roles in driving popularity among younger consumers. The most influential e-commerce livestreamers such as Viya and Li Jiaqi have become stars in their own right, and celebrities from both China and overseas (such as Kim Kardashian) have been getting involved as a way to make themselves and the brands they represent more relatable to consumers.

2. Key opinion leaders, consumers and amateurs

Influencers have been key drivers of livestreaming’s success in China, as they not only endorse products but also sell them to consumers through their own online shops on established e-commerce platforms. Chinese consumers have a preference for obtaining product information and recommendations from trusted sources, and the “key opinion leader” (KOL), denoting a celebrity or popular internet personality with a large following, has been a mainstay of China’s influencer scene for some time.

The past year saw the emergence of more diverse categories of influencers, particularly the much-talked about “key opinion consumer” (KOC), typically with a much smaller following of young peers and acquaintances who may be more readily influenced by the KOC’s recommendations. Also joining the ranks are “key opinion amateurs” (KOAs), who occupy a middle ground — less specialized than KOLs, but with more influence than KOCs, and who can play an increasingly important role as creators to satisfy the bottomless demand for fresh content from Chinese platforms.

These new types of influencers can help to secure the trust of young consumers who are more wary of KOLs in the wake of scandals over fraud, data manipulation and other troubling practices among those who make a living from promoting products.

3. Chills through the entertainment and advertising industries

Meanwhile, the entertainment industry faced a “capital winter” throughout 2019, with nearly 1,900 TV and film studios and production companies shutting down by November — the result of falling investment from financial backers and advertisers and increasing competition from online platforms, especially those offering newer formats such as short video and livestreaming.

Adding to the constraints this year was the politically sensitive 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, which saw numerous restrictions on content. Some of these were very explicit, such as the ban on overly-entertaining dramas in the run-up to the anniversary on October 1, while others operated in a murkier fashion, such as the censorship of completed films such as “Better Days” (少年的你) and “The Eight Hundred” (八佰)— the former scored a release date several months after its premier was canceled, but the latter been in limbo since June. In all cases, parties involved have suffered financial losses, and the climate towards new productions remains shrouded in uncertainty.

The climate of restriction was not limited to the anniversary either, as authorities issued a slew of regulations cracking down on content both before and after the big date. These ranged from prohibitions on certain types of content in youth programming to plans to strengthen supervision of livestreaming e-commerce broadcasts and live performances.

4. The commerce-linked boom in short video

More than 70 percent of China’s mobile internet users engage with short videos. And while TikTok made waves around the world for its mindless entertainment and youthful orientation, its Chinese counterpart Douyin and other short-video platforms emerged as much more comprehensive destinations for a variety of content running the gamut from educational series to professional short dramas produced for the vertical screen.

“Douyin has a fairly affluent demographic, and they’re generally very globally aware and sophisticated consumers” says Arnold Ma, CEO and founder of digital marketing agency Qumin. Douyin and other short-video apps are much friendlier to e-commerce than Western social media platforms, and brands have taken advantage of the ability to open branded accounts and establish e-commerce accounts that enable a seamless shopping experience. Douyin also features rankings of top-performing brands by various categories, which allows brands to learn about what works best in format among viewers.

5. Brand integration with slow-living trends

The hectic pace of life in contemporary China has created a space for entertainment that is relaxing, aspirational and subtly educational, with a rising demand for content focused on food, travel and daily life. Unscripted programs such as the Airbnb-sponsored “Adventure Life” (奇遇人生), “Back to Field” (向往的生活) and “Yacht Life: Love the Ocean” give viewers insights into new experiences and offer numerous opportunities for brand integration through organic product placement that blends into the content of the shows, making it more palatable for audiences.

Also driving the slow-living trend are influencers such as Li Ziqi, the hugely popular vlogger whose videos showcase traditional techniques of food preparation and handicraft production amid an idyllic rural background. Although Li has thus far declined to place brands directly in her videos, other avenues for brand cooperation include offline events and product collaborations that can be featured on her e-commerce stores.

6. Entertaining brand placements

As traditional advertising declines in China, the merger of brands with entertainment is evolving rapidly, with content producers and brand owners showing great openness to experimenting with technology and creativity to link content and commerce. One review of brand integration by Chinese industry news outlet Huayu identified 15 types of brand placements frequently used in Chinese media, ranging from traditional pre-roll ads to more recent innovations, such as tech-driven pop-up ads that tie into plot points in a drama as it unfolds onscreen, or mid-broadcast interstitials that see actors from a show endorsing a product while still in character. Brands are increasingly written into storylines, and viewers are unlikely to mind well thought out efforts.

On popular reality shows, brands are promoted not only via traditional methods such as title sponsorships and product placements, but also through more direct integrations involving the stars and brands. Talent competitions such as iQiyi’s “Rap of China” feature contestants performing in music video spots promoting some of the show’s sponsors, including foreign brands such as McDonald’s and Nivea. This summer, iQiyi premiered the first interactive online ad on the show with a spot for Clear Shampoo that allowed viewers to choose which contestant they wished to see perform an extended rap.

7. Brand collaborations

The crossover (跨圈, kuajuan, literally, “stepping out of the circle”) has become one of the year’s buzzwords in Chinese marketing. In today’s crowded consumer market, brands are constantly seeking to break out of the constraints imposed by their core products to find new ways of reaching more consumers. One result has been a huge uptick in collaborations between brands on a creative range of joint products, such as confectioner White Rabbit’s skin-care partnership with fragrance brand Scent Library, or M.A.C Cosmetics’ lipstick collaboration with Tencent’s mobile game “Honor of Kings.” Successful collaborations such as these not only create a spike in demand for limited-edition products, but also boost publicity for the brands involved through the creativity of the endeavors.

Chinese culture has been an especially fertile ground for collaborations, particularly those that involve major cultural institutions such as the Palace Museum in Beijing. National heritage is also being tapped for its entertainment value through a number of documentary-style reality shows such as CCTV’s “National Treasure” (国家宝藏), which have grown in popularity among younger audiences.

8. Offline experiences

While much of brand integration with entertainment takes place online, the desire for new experiences among young Chinese consumers creates further opportunities for brands to leverage sponsorships and work with China’s leading tech companies on cross-sector marketing. Musical talent competitions offer obvious opportunities for concerts, such as the series sponsored by War Horse Energy Drinks in connection with its sponsorship of season three of “Rap of China” this summer. But other types of content can be expanded into the real world as well: The fashion-oriented reality show “Fourtry” (潮流合伙人) is launching pop-up boutiques in a Shanghai department store to sell goods featured on the show, while the tea culture that features prominently on drama “When Shui Met Mo: A Love Story” (水墨人生), was leveraged by sponsor InWe Tea, a trendy chain that transformed one of its locations into a themed pop-up shop with the show’s stars on hand.