This is the third part of a three-part series in which we take a look at Hong Kong cinema from the time of the 1997 changeover up to today. Read Part I and Part II.

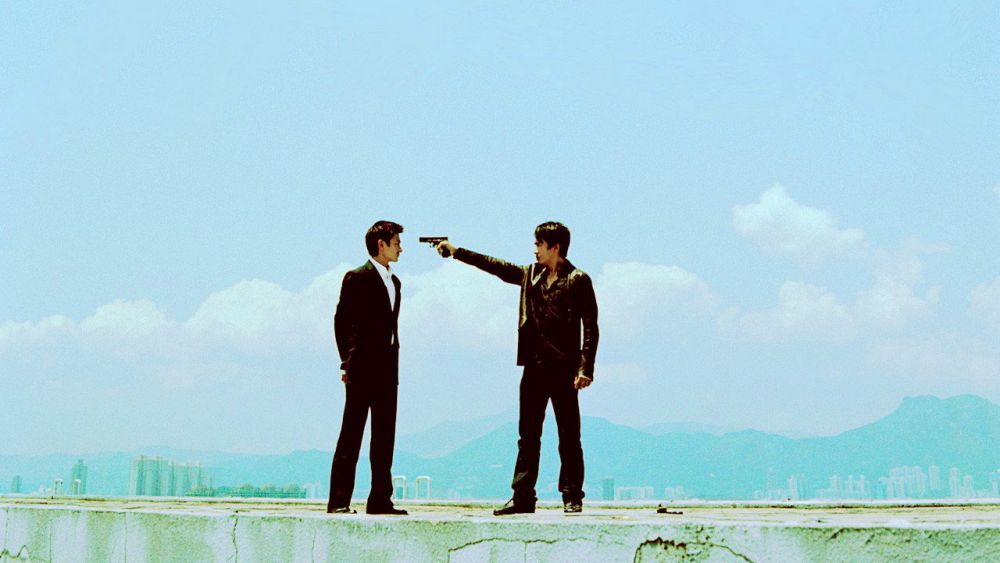

Bishonen.

In 1993, the Hong Kong film industry packaged a number of films, which played at festivals and museums around the world. Representatives from the film industry accompanied the films; when this touring program played in New York City, the opening night film was Johnnie To’s “The Heroic Trio” (1993), starring Maggie Cheung, Michelle Yeoh, and the late Anita Mui. Introducing the film, there were constant references to the “high octane” energy and the “kinetic” style as characteristic of Hong Kong cinema. And there was a definite sense that the qualities that were to be emphasized were the energy and the style, rather than any sense of political meaning.

That energy and style would prove to be captivating to many filmmakers around the world. It is widely known that Quentin Tarantino has been enamored of Hong Kong cinema, and Martin Scorsese has been a vocal advocate for Hong Kong cinema, certainly starting with the films of John Woo. (When “The Killer” was shown in the US, it came with the announcement that it was “presented” by Martin Scorsese.) But the meanings behind so many of the films have not been explored, as the assumption of the films as simply belonging to the genre of action cinema has been so prevalent.

For that reason, many filmmakers have been overlooked in most discussions of Hong Kong cinema. For example: Mabel Cheung. She has never really worked in what many regard as the typical Hong Kong genres of action films or thrillers; instead, she has crafted a series of dramas and comedies featuring women as central figures. Perhaps her most ambitious film was made right at the time of the Hong Kong changeover, the historical epic “The Soong Sisters” (1997). Though heavily fictionalized, the film did provide a look at one of the central families in 20th Century Chinese history.

The next year, Cheung directed “City of Glass,” with a plot derived from the Billy Wilder film “Avanti!” (1972): two people meet in a foreign country, where they have come to bury their parents. To their surprise, they discover that their respective parents (her mother, his father) had been having an affair which lasted decades, always claiming the same business meeting during the summer. In “City of Glass”, the locale has been moved to London, and there is a nostalgia for the British way of life, which had been a dominant factor in Hong Kong culture throughout the 20th Century.

Yonfan is a director from Singapore, who has worked in China and in Hong Kong; he is notable for being an outspoken and “out” gay director. “Bugis Street” (1995) was a look at the denizens of the infamous street in Singapore noted for its transvestite prostitutes. “Bishonen” (1998) was set in Hong Kong, and told a romantic tale of a gay hustler who falls in love with the new policeman on the beat. As with Stanley Kwan’s “Hold You Tight,” the decidedly upfront depiction of homosexuality was part of the Hong Kong cinema’s defiance in terms of maintaining the relaxed censorship which had been central to the film industry.

During the 1980s, the critical attitude towards Hong Kong cinema from the West emphasized the immense commercial resources at play: it was looked on as another Dream Machine, as potent as the cinema of old Hollywood. In many ways, this view of Hong Kong cinema played on a nostalgia for a unified popular culture, at a time when Hollywood had diminished in terms of its popular culture reach. When independent cinema came to the fore, with its lack of strict narrative and structural cohesion, there was a deep-rooted need to assert the conditions of a popular culture phenomenon which remained connected to a mass audience. In short, it was becoming difficult to talk about movies in simple terms of mass appeal. And Hong Kong cinema seemed to fill a void.

But it would be naive for us to simply align ourselves to the view of Hong Kong entertainment as a panacea for popular culture’s revival. It would also be rather patronizing to try to impose meanings which might not be inherent in the films themselves, as if the films were not the result of very careful craftsmanship and conscious artistry.

Since there are directors such as Mabel Cheung and Ann Hui who have been quite explicit in their political views, to try to align every director with a political agenda would be disingenuous. When I started to research this essay, as I tried to remember some of the films which I had seen, and began researching some of the directors, I was struck by the differing responses which came over time.

Recent critics have tried to look at the Hong Kong film industry since 1997 in terms which are much more political than the critics who deigned to regard Hong Kong as the New Hollywood in the 1980s. But is that response valid, or is it wish fulfillment on the part of those who want to find a political statement on the very conflicted values found in Hong Kong’s position as the capitalist avatar of the New China?

Right now, Hong Kong cinema remains an industrial complex which continues to make entertainment of many genres. Perhaps the Golden Age of Hong Kong cinema has passed, but in all likelihood the changes in Hong Kong cinema’s efficacy have much to do with the changes in technology as much as with anything else. But the films themselves, both the ones featured and the many more which have been produced, do tell, not a single story of political attitudes, but a multifarious story of many differing cultural and social impulses, which have combined to continue the vitality of this most anomalous entity, the commercial cinema of Hong Kong as it faces its future.

Daryl Chin is a co-founder of the Asian-American International Film Festival. He is a multimedia artist, critic and curator. He was Associate Editor of PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art from 1989 to 2005. He was on the Board of Directors of NewFest (The New York Lesbian and Gay Film Festival) and Apparatus Productions. With Larry Qualls, he created over 30 theater/performance pieces from 1975 to 1985.