In the first part of a three-part series, we take a look at Hong Kong cinema from the time of the 1997 changeover up to today.

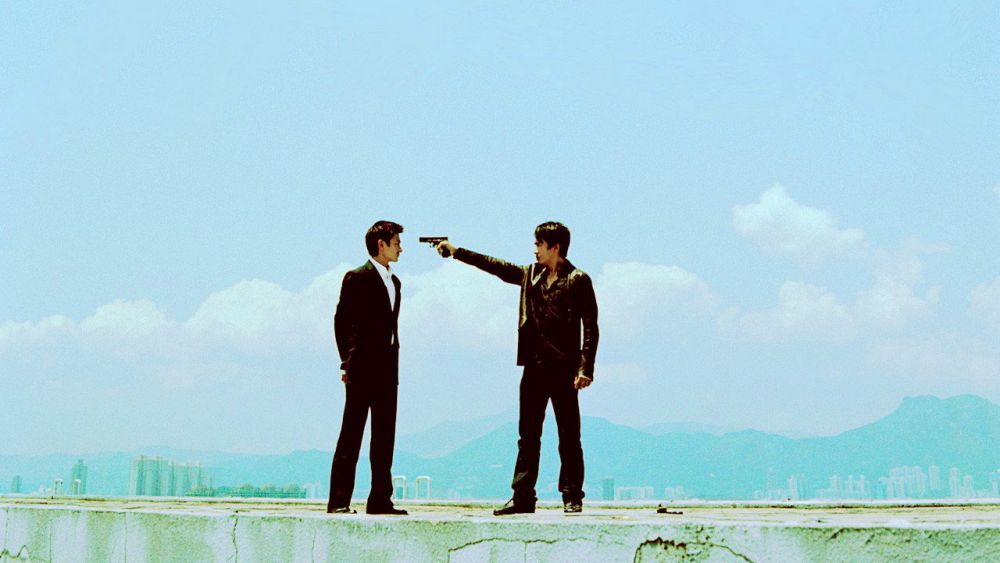

Infernal Affairs.

By the end of the 1960s, Hong Kong’s film industry was booming. It had become world renowned for the brashness of its action pictures, created with such exuberance and crafted precision. The stunts in those movies have become legendary. In addition, there was a true proliferation of films of all sorts, including comedies and romances and dramas.

Starting in the 1980s, the Hong Kong cinema helped to reestablish many genres, such as gangster films, crime dramas, and kung fu comedies, which would have an impact worldwide. Yet the freedom which Hong Kong cinema experienced was constrained by the contours of unrestricted commercialism.

In the summer of 1997, the sovereignty of Hong Kong was set to undergo a change, when the island and the New Territories would go from being part of the British empire to being claimed as a region of the People’s Republic of China.

The ramifications of the changeover were, at the time, incalculable; it was not known what effects on the economic, political, and social life of Hong Kong this changeover of government would have, since the changeover seemed to represent a total break with traditions of over a century. Hong Kong’s position as one of the remnants of British colonialism in Asia now would be adjudicated as an annexation of Chinese rule.

Thinking back to that period, there was a sense of panic, as many Hong Kong residents tried to find a place to move within the British Commonwealth. There were quotas set up, as many Commonwealth countries feared a mass exodus to their shores; in particular, Australia and Canada were countries that seemed to be very wary of the presumed influx of Hong Kong residents. This political panic exposed a lot of the inherent prejudices of the British Commonwealth, prejudices which continue to roil the politics of Great Britain to this day.

But the film industry in Hong Kong was in a state of suspension. Many talents had come to Hollywood, starting with John Woo in 1986. Chow Yun-Fat, one of the biggest stars in Hong Kong, was negotiating to do films in the US; “Peace Hotel” in 1995 would be his last Hong Kong production for several years, as he negotiated to make films outside Hong Kong. However, no one had any idea exactly what changes would occur, and that unease caused a great deal of anxiety.

The producer and director Johnnie To has been an astute analyst of the situation of the Hong Kong film industry. As he has noted, Hong Kong itself never was a democracy. It was a colony, and the government was controlled by people who had been appointed by Great Britain.

Because of the lack of direct contact, that governmental control was never too rigid, with the illusion of great freedom which was more the result of benign indifference than political intention. But would Chinese rule bring about fundamental changes to Hong Kong? The Chinese government had been notorious for its autocratic control over all aspects of Chinese culture, and the fear was that this control would diminish the creative impulses of the film industry. That would not be the case.

For one thing, the People’s Republic of China was undergoing its own changes, as rapid industrialization was causing societal upheavals. The desire on the part of the Chinese government to encourage economic growth meant that the commercial success of the Hong Kong film industry was something to emulate rather than something to curtail. And so the Hong Kong film industry found itself continuing in its productivity, though faced with difficulties caused by the rapid technological changes in which the model of theatrical distribution has been challenged, a challenge faced by motion picture industries around the world.

For all that, to try to extrapolate political meanings behind much of the Hong Kong cinema after 1997 is rather tricky, because the meanings behind so much of Hong Kong cinema prior to 1997 were never explicitly political; to read into these films with the the imposition of a political agenda can lead the viewer to a diminished sense of the qualities of these films, which rely on skillful craftsmanship to provide kinesthetic entertainment.

A case in point might be “Infernal Affairs” (2002), certainly one of the most famous of Hong Kong thrillers, directed by Andrew Lau and Alan Mak. The intricate machinations of the plot involved the slow revelation of conspiratorial impostors; as the opposing teams representing law enforcement and the criminal underworld are shown to have agency in terms of undercover representatives, the sense of a nocturnal society layered in corruption becomes inescapable.

Immediately upon its release, it was obvious that “Infernal Affairs” was exceptionally well executed, with a relentless pace which allowed the most outlandish revelations to seem inevitable. The fame of “Infernal Affairs” was only enhanced when Martin Scorsese decided to craft an American remake, “The Departed” (2006), which would become one of his most celebrated movies.

But the differences of the two movies are instructive. Scorsese’s version tries to ground the plot in a carefully constructed social setting, taking care to develop a realistic picture of Boston’s ethnic enclaves. By contrast, “Infernal Affairs” seems to take place in a fantastical city of gleaming surfaces, and the actual workings of the police and the triads are abstracted, so that the similarities of the operations become obvious, and the question of moral equivalence is emphasized.

From “Infernal Affairs,” what can be made in terms of the question of the political position of Hong Kong society? On the most basic level, there is the inference that all political systems are similarly tainted, open to corruption and conspiracy.

Fruit Chan‘s “Made In Hong Kong” (1997) was a film made at the time of the changeover in Hong Kong; the depiction of low-level triads attempting to carry out various small scale activities could be seen as a portrait of the ways in which so many business ventures tried to continue under the radar of governmental oversight which was expected to overtake Hong Kong. Yet the escalating explosions of violence provide the kind of visceral excitement which was a hallmark of Hong Kong cinema. Were we to make a symbolic connection to the suppressed emotions waiting to explode?

That is the problem with trying to discern symbolic meanings behind commercial entertainment. This becomes clear when contrasted with an overt piece of agitprop, Ann Hui‘s “Ordinary Heroes” (1999), which attempts to give a panoramic view of political protests in Hong Kong, dating from the 1970s. Weaving together documentary footage with reenactments, this passionate assemblage is an eclectic mix, with wildly disparate segments, so that there is no sense of an even flow, but there are hectic moments of sharp insight.

Ann Hui, of course, has been noted for her blunt style, which was featured prominently in her early films, such as “God of Killers” (1981) and “Love in a Fallen City” (1984); perhaps the most famous example of her political style was found in “Boat People” (1982), which at the time seemed an almost hysterical cataloguing of the many injustices that surrounded Vietnam at the end of the war with America.

There is always a fervor to her concerns, and this was particularly the case with “Ordinary Heroes.” The reason it’s important to point out the overt political message of the film is that to suggest that the only way for filmmakers to try to get out a political message is through symbolic intervention within genre formulae does a disservice to the possibilities within the Hong Kong film industry.

An artist like Ann Hui, who continues to work with political content, has continued to work in Hong Kong. A recent film, “A Simple Life” (2011), is a touching comedy-drama that addresses issues of aging and class in Hong Kong life. Her attempt at a very broad overview of political protests in Hong Kong in “Ordinary Heroes” remains a commendable achievement, and it should not be minimized because of the uneven quality of the film.

Daryl Chin is a co-founder of the Asian-American International Film Festival. He is a multimedia artist, critic and curator. He was Associate Editor of PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art from 1989 to 2005. He was on the Board of Directors of NewFest (The New York Lesbian and Gay Film Festival) and Apparatus Productions. With Larry Qualls, he created over 30 theater/performance pieces from 1975 to 1985.