This is the second part of a three-part series in which we take a look at Hong Kong cinema from the time of the 1997 changeover up to today. To read Part I, click here.

Stanley Kwan’s ‘Rouge.’

Johnnie To has been working in the Hong Kong film industry since 1978; he has been a director and a producer. In 1996, he created Milky Way Productions in association with Wai Ka-Fai; it has become one of the premier motion picture companies in the period since the changeover. “The Mission” (1999) was one of his first films made in the period immediately following the political changes in Hong Kong, and it remains one of his most accomplished films.

As usual with a lot of the plots in these films, there is a great deal of improbability, but the rapid pace makes it almost impossible to apply logic when there is so much action. The story seems simple: a triad boss hires five killers as bodyguards. But there are many twists to the plot, as it becomes increasingly clear that the relationships of these men are not what they seem.

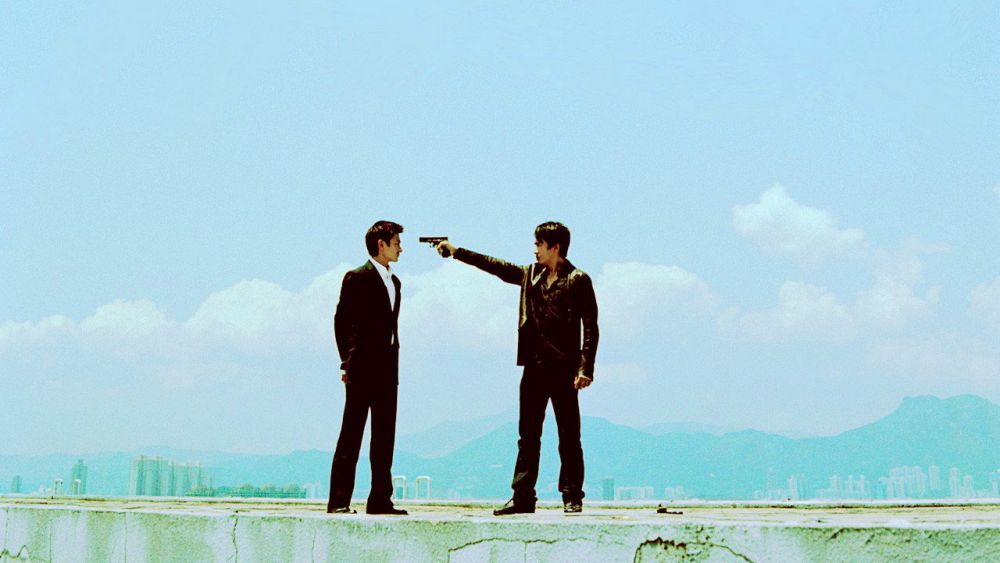

But it’s hard to say exactly what political message can be gauged from “The Mission”; of course, it’s a depiction of loyalty, but in the case of Johnnie To, his later trilogy, “Election” (2005), “Triad Election” (2006) and “Exiled” (2006), has a more directly political statement. Though set within the precincts of the triads, these films use the idea of governance as the germinal plot, with the question of who controls the organization and how the organization is to be run making not-so-veiled allusions to the then-current situation of Hong Kong.

As one of the most prominent figures in Hong Kong’s film industry, Johnnie To has given many interviews, and he has expressed his skepticism about the need that many critics have to politicize what is happening in Hong Kong. Of course, films cannot help but reflect the society from which they came. Johnnie To is an example, in that his “Election” trilogy made many explicit connections to the actual political situation in Hong Kong during 2005 and 2006; for those of us who are not Hong Kong residents, some of the references may seem obscure, but the films do succeed as thrillers irrespective of the overt political content.

Stanley Kwan was one of the first Hong Kong directors to gain “art house” renown in the West with his film “Rouge” in 1987. By that point, the Chinatown circuit was in the throes of collapse, which created a very different commercial situation for films from Hong Kong. (Quite simply: since the end of the 1940s, there were movie theaters in the Chinatown areas in the major cities of the US, Canada, and the UK, and all films produced commercially in Hong Kong would circulate in those theaters; this was a contractual condition, and it precluded any Hong Kong film from getting distribution in any other way.)

One of the highlights of Kwan‘s work has been his sensitivity to performers, in particular, to his actresses, and this can be seen in “Center Stage” (1989) with a performance by Maggie Cheung as the silent film star Ruan Ling-Yu which remains a career peak.

“Hold You Tight” (1998) was Kwan’s first movie after the changeover, and it remains one of his most provocative movies. It is also quite problematic, because the narrative is fractured into flashbacks, and there are times when narrative coherence is lacking. It also complicates matters that the actress Chingmy Yau is playing two parts, in different time periods (the fact that one character looks like the other character is the point: a man becomes obsessed with a woman who looks like his dead wife), but there are times when it is hard to differentiate the times.

“Hold You Tight” is perhaps best remembered for the opening: a scene of sexual encounters in a gay spa. The shock of the opening then becomes a series of complicated storylines in which people become romantically entangled, both in the past and the present. One aspect of the film which proved highly amusing was the emphasis on travel: it seemed as if the major characters were always waiting to fly off to another place, and this seemed to suggest that Hong Kong was filled with a nomadic population. Yet Hong Kong, as home, seemed to be a city of constant flux, and the complications of the plot seemed to mirror that fact.

Of course, testing the limits of sexual representation was one way of seeing if there had been changes to the problem of censorship; the Hong Kong film industry had a system of ratings, and there were always subjects which were considered quite incendiary.

Though to us, the many films about triads and the hostilities between rival organizations seem as stylized as the workings of the typical gangster film, but in Hong Kong, these films receive a great deal of scrutiny, because the corruption which is revealed is considered detrimental to the image of Hong Kong. For that reason, a great many of those films wind up with very restrictive ratings, so that the audiences for those films are only for adult audiences. It is feared that these films about the triads would prove to glamorize criminal activity, so children must be kept from seeing them.

Daryl Chin is a co-founder of the Asian-American International Film Festival. He is a multimedia artist, critic and curator. He was Associate Editor of PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art from 1989 to 2005. He was on the Board of Directors of NewFest (The New York Lesbian and Gay Film Festival) and Apparatus Productions. With Larry Qualls, he created over 30 theater/performance pieces from 1975 to 1985.