A birth, a death, a pilgrimage. A film about the 1,200-mile journey of a pregnant woman, a butcher who wants to atone for his sins and a rag-tag band of villagers who go on foot from their small village in Tibet to the sacred Mt. Kailash has become a surprise winner at the Chinese box office.

It has also found a cult following among an unexpected audience — China’s venture capitalists and startup founders.

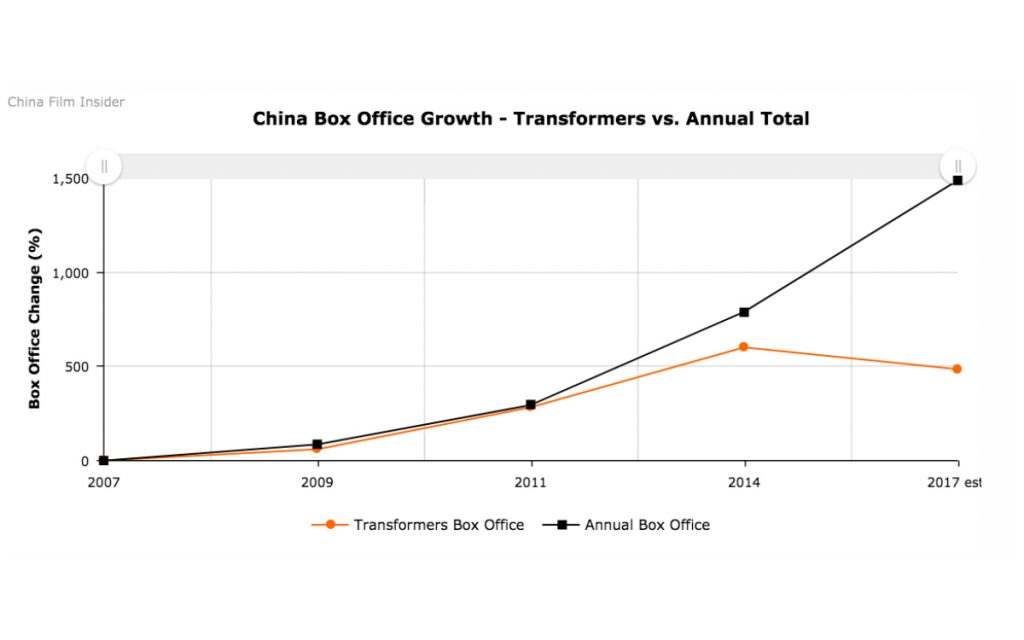

The low-budget docudrama, “Paths to the Soul,” has been more profitable per screening than Hollywood juggernauts such as the latest “Transformers” movie, which opened in late June. “Paths to the Soul” raked in over 40 million yuan ($5.88 million), or nearly three times its production cost, during its first 11-day run despite being shown in less than 2 percent of theaters in the country.

There was no script or musical score and “the actors,” who really did make the year-long journey on foot with only a supply wagon hitched to a rickety tractor, prostrate all the way through in an act of Buddhist devotion.

They travel wearing thick aprons made of yak hide and wooden planks tied to their palms. Every few feet, they raise their hands high above their heads in respect for the Buddha, then lower their worshipping hands to their forehead and then to their chest before diving into the ground, touching the earth with their foreheads. To an outsider, the ritual looks like bodysurfing on solid ground. While they chant a simple mantra, devotees lie flat on their stomachs with their hands bent at their elbows, pointing toward the heavens in a sign of prayer. Then they stand up and repeat these steps as the summer’s scorching asphalt roads turn into slippery ice-covered tracks in the winter. Many moviegoers said they were captivated by the pilgrims’ altruistic motive of wanting to pray for the happiness and well-being of their loved ones at one of the spiritual epicenters for Buddhists. Mt. Kailash, in northwestern Tibet, is also regarded as the site of philosophical battles between the Tibetan yogi and the poet Milarepa and his opponents.

But why has this austere film, produced on a shoestring budget, struck a chord with China’s well-heeled venture capitalists and business leaders?

Many who were invited to a recent private screening of the film by the founder of Hillhouse Capital, one of China’s most successful, eagle-eyed venture capital firms. The founder noted that the physically and spiritually transformative pilgrimage was akin to starting one’s own venture.

“The pilgrims encountered many frustrations, including a car accident, illness and even a landslide, but they continued calmly without getting upset,” said Wang Mengqiu, managing director of Crystal Stream Capital. “It shows the true meaning achieving a state of mental equilibrium in everyday life. And the hardships of entrepreneurship are also a form of self-cultivation.”

Director Zhang Yang depicts the grueling journey without over dramatization, like a master painter using the lightest brush strokes to evoke emotions. Zhang, known in the art-film world for his works such as “Shower” and “Spicy Love Soup,” keeps the camera at a distance, showing how the devotees inch their way across wheat fields and urban jungles. The absence of a music score only strengthens the film’s message about striving for serenity, magnifying the powerful echoes of nature.

The only sounds that disturb the silence are the clatter of wooden clogs and the scraping of the pilgrims’ palms and knees on the ground.

For Zhang Lei, the founder and CEO of Hillhouse Capital, this silence “was as deafening as thunder.”

“When I was watching the film, I thought of some of my friends, and although what we are striving for isn’t what the pilgrims were pursuing, at some level, we are all pilgrims on a journey seeking self-cultivation. So at a subconscious level we can all relate to this experience,” he said.

A spiritual connection

The film has also prompted some soul-searching among the educated, middle-class in China. It was rated 7.8 out of 10 on Douban, a website similar to Rotten Tomatoes that relies on user feedback. The ratings showed that this $2 million production had punched way above its weight. In comparison, Chinese audiences gave the $217 million blockbuster “Transformers: The Last Knight” a dismal rating of 4.8.

“There are no intentional twists and turns, or emotional turmoil, but there is the power of reality and vivid personalities,” wrote one viewer on Douban.

“The film showed us what purity of heart and the purity of faith means,” another wrote.

“Paths of the Soul” has fueled divided discussions about Tibetan Buddhists, their religious devotion and how such piety should be valued in modern society.

Zhang Yang, the film’s director, said he was strict about being restrained in order to avoid any over-interpretations of Tibetan Buddhism to satisfy the curiosity about Tibetan culture among outsiders.

“I’ve seen many pilgrims on the road and the rituals are part of their everyday life. There is nothing extraordinary but repeating the procedure itself is powerful enough,” Zhang said. “We tried from the beginning to avoid (telling the story from) the perspective of Han nationals,” said Sun Li, the art director of the film.

Zhang said there was no script for the film, except a rough idea of the characters he needed. In 2013, Zhang’s team visited a small village at the Tibet-Yunnan border, where he met such characters among a group of local villagers.

It wasn’t difficult for Zhang to convince the villagers to be in the film because they all yearned to go on a pilgrimage and thought of it as a natural part of life, although they didn’t know anything about making a film, the director said.

Among the villagers was a 23-year-old woman named Tsering Quzhen who decided to go on the pilgrimage despite being late in her pregnancy. Tsering gave birth about one-and-a-half months into the journey and the entire spectacle was caught on film. “I was shocked and in awe when the baby came to this world,” the director wrote on his diary that day.

Following in the footsteps of the birth came death. When the 72-year-old grandfather Yang Pei passes away at the foot of Mt. Kailash — one of the few fictional plot elements added by Zhang to create a contrast — viewers are left pondering the idea of impermanence that recurs throughout the film. The pilgrims sit around Yang silently and with equanimity as he lets out his final breath, illuminating the Tibetan belief that hysterical cries or sobbing could disturb the departing conscience of the diseased (unlike the Christian notion of a soul). “This is a philosophy they have learned since they were young,” the director said.

Unlike most of his other film schedules, which were intense, Zhang’s team adopted a slow pace. They spent nearly one year on the road to shoot and collect stories from people they met to be dramatized into the film.

In one scene the film focuses on a couple traveling with a donkey. They were carrying all of their heavy baggage on their own shoulders, while putting only a light load on the beast. The wife tells the director that for them, the donkey was like a family member and they wanted to finish the pilgrimage with it, so they couldn’t exhaust the animal.

The film crew also spent time chatting with other pilgrims and shooting the daily lives of ordinary Tibetans. The Tibetan staffers sat in a circle every night chanting Buddhist scripture.

Finding one’s self

Born in 1967, Zhang is a leading player in an art movement known for works rooted in reality. He was widely recognized for his 1999 independent production “Shower,” which received nominations and awards at international film festivals including the International Critics’ Award at the Toronto International Film Festival and the Best Director Award at the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain.

But Zhang’s career was in the doldrums in 2010 as his attempts at producing commercial films such as “Driverless” and “Full Circle,” turned out to be flops. “Full Circle,” a story about a nursing home, was released in 2012 with a 20 million yuan investment. It earned only 5 million yuan at the box office.

“After ‘Full Circle’ I felt I needed to take a break, otherwise I would have lost myself,” Zhang said. “I needed to think quietly and then come back to make something pure.”

Zhang eventually made his return with “Paths of the Soul,” which premiered at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival. The film became an instant hit in the festival circle, but it struggled to raise enough money for marketing and distribution in China until late 2016.

The time spent on the film changed Zhang’s appearance. His smooth, clean-shaven face has turned rugged and weather-worn like those of the pilgrims, said Li Li, chairman of He Li Chen Guang International Culture Media Co., one of the film’s distributors.

But according to Zhang, his own transformation during filming ran much deeper. He said he had freed himself from the struggle between pursuing artistic excellence and commercial success, and doing well at the box office was no longer a big concern for him. “I’d like to keep a distance from investors so that I can hold on to my freedom as an artist,” he said.

“Shooting ‘Paths of the Soul’ was akin to going on a pilgrimage for myself. It made me understand that I must try to forget all I have learned and try to understand the art of film direction again — to shoot everything like it’s the first time,” he said.

—This article originally appeared at Caixin Global.