Did Bilibili, who now holds not only content copyrights but also the government green light, cross the political line like its competitor did? One would need to inspect all of the missing content to find out.

On the morning of July 13, users woke up to find that the majority of foreign TV shows and films had disappeared from Bilibili, an online video sharing and social platform. Months before the 19th Communist Party Congress, China’s tech firms had already been feeling the chill of media regulation. Real-name registration was enforced for users and many companies hired extra staff to screen online discussions.

Bilibili announced (in Chinese) the next day that the blackout was a result of “self-censorship” without elaborating on what that entailed. There was no notice from state media watchdogs. Fans flocked to online forums fathoming what might have happened, lamenting Bilibili’s future prospects in an increasingly strict media environment.

In the past eight years, Bilibili has evolved from an obscure and sometimes marginalized community for anime, comic, and gaming (ACG) fans into a “spiritual home” for over 7,000 culture groups that has turned the heads of Chinese tech titans. A whopping 90% of its users are under 25, who post, view, and comment on videos in the form of danmu, real-time audience commentaries that roll across and atop the streamed videos.

Users trying to access foreign TV shows and films on Bilibili after July 12 are met with the message: “This video has disappeared”

The Pessimists

Netizens came up with two theories to make of Bilibili’s content blackout—copyrights infringement, or media crackdown.

For years, the video sharing site thrived under contribution by the so-called “porters”—fans who volunteer to transport programs from other websites once a new episode is released. This speculation was dismissed by many because much of Bilibili’s foreign content was long gone by the time of the incident. In recent years, China has been stepping up its copyrights oversight. Well-oiled video streamers like iQIYI, Youku-Tudou, and Tencent Video, who respectively belong to the Chinese tech trinity of BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), started to gobble up exclusive licensing deals for popular content, forcing smaller sites like Bilibili to clean up.

Moreover, Bilibili has been buying its own content to meet the needs of its core ACG users. But owning copyrights doesn’t mean Bilibili is free to stream anything. Among the videos that got pulled down in July were shows that Bilibili had already bought, including the smash hit Japanese TV series Shinya Shokudo.

This is where the theory of media crackdown came into play. In China, foreign programs can be pulled if they are deemed too popular or pose a threat to domestic content. Foreign entities are already restricted from publishing content online without having a local media partner.

Chinese companies are not immune either. In 2014, the nation’s media watchdog State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT) unveiled a tough stance to regulate video streaming services: If websites do not seek a license from SAPPRFT for their foreign programs by April 1, 2015, they won’t be able to broadcast them online. By the end of that April, shows like The Good Wife and The Big Bang Theory were yanked from a number of popular video sites.

Obtaining that audio-visual publishing license isn’t easy. “Everyone is circumventing the system, that is, settling the problem by acquiring a company with a broadcasting license,” Chen Taifeng, vice president of Yixia Technology, Weibo’s official live streaming partner, told local media.

Bilibili actually holds that official license. Earlier in June, Bilibili’s arch-rival AcFun, along with Sina Weibo (NASDAQ: WB) and Phoenix New Media (NYSE: FENG)’s news portal ifeng.com, were asked to stop streaming videos for they have “provided audio-visual services without gaining the appropriate certificates,” SAPPRFT said in a statement. There was another verdict: These sites have been screening many politically-related programs that do not conform with state rules.

While Bilibili was undergoing self-censorship over the night of July 12, AcFun also shuttered its entire TV show and film channel. The lack of government approval might have explained why AcFun suffered a bigger loss from this wave of media crackdown, says Yiyi Yin, who researches pop culture and cinema studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Did Bilibili, who now holds not only content copyrights but also the government green light, cross the political line like its competitor did? One would need to inspect all of the missing content to find out.

The Optimists

On October 9, three months after Bilibili’s self-censorship exercise, third-party data firm JPush published a seemingly perplexing number: Contrary to the pessimistic public view, Bilibili saw an average of 553,000 new users added to its mobile app each day from July 14-31.

“Foreign films and TV shows only make up about 5% to 10% of Bilibili’s traffic, so the unshelving will not create a noticeable impact,” Bilibili responded in a statement. The user growth during this period was reflective of the website’s steady uptrend in user number in the last six months, according to analysts.

“Most users are still used to watching original user-generated content,” Bilibili adds. This means that the UGC-driven site does not have to rely on licensing expensive programs—which the media regulators mainly target at the moment—to acquire users like conventional video streaming services do.

“Compared to other websites who are betting big on content licensing or producing their own, the impact of heightened media regulation on Bilibili is actually not that obvious,” Kenneth Tang, who oversees JPush’s research division, told TecNode.

Instead of calling it a video streaming website, some have proposed to call Bilibili a social platform for youths. The experiences of a video inundated with text and an originally pleasing video remade mad perplexes the older generations. But to young Chinese, mashup videos are outlets of fandom and creativity and danmu, which Bilibili has popularized in China, acts as a participatory tool.

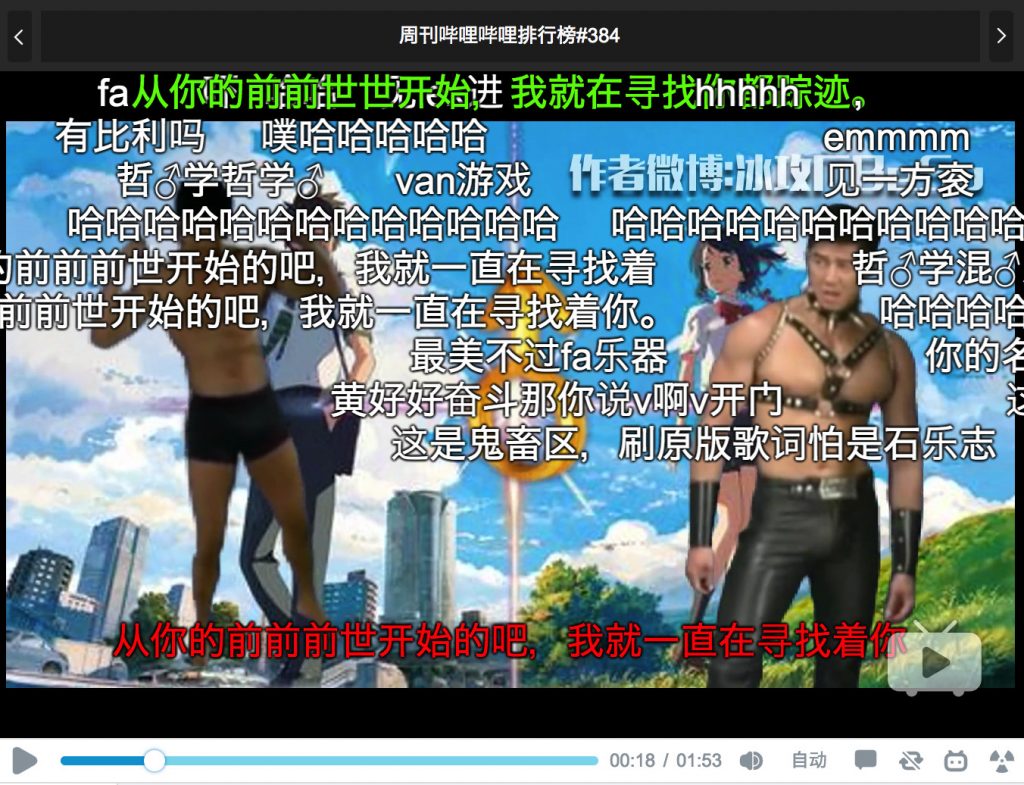

A mashup video of the blockbuster Japanese animated movie Your Name posted on Bilibili, with danmu flying by

Some leave danmu on to find a sense of companionship as they sit alone in front of the screen. Others, who have seen a video first without danmu, come back for the commentary which are often no less incisive than professional film critiques. To maintain the exclusiveness and “quality” of its user base, Bilibili sets a high bar for newcomers: One must either receive an invitation or score 20/40 in a Bilibili-related quiz under 120 minutes to successfully register.

User participation isn’t limited to pop cultures. Yin’s research suggests that the mostly entertaining site can also inspire public discussion. “As a subcultural space, Bilibili enables youth to organize their own community. In addition, it provides the technological infrastructure for the youths to play with certain form of public discussions.” The research examines the instance in which the court hearing on Kuaibo was uploaded onto Bilibili, where young users “create, entertain and celebrate jokes and myths around the case.”

“When I first knew about Bilibili, I had the same reaction as most post-80s and even post-70s, that danmu is against human nature,” said Wang Shiyu, managing partner of one of Bilibili’s investors K2VC, in his blog (in Chinese). “But then I saw Bilibili’s numbers. Besides the millions of daily active users, the number of commentaries and activeness of video uploaders is very good too. Users are also extremely sticky. This boosted my confidence in investing in it.” As of July, the site boasts 100 million active users.

The Future

Though anime is still the most consumed video type on Bilibili, new channels such as technology and lifestyle have been added to appeal to China’s next generations. Old users protest at the move, complaining that it would “pollute” Bilibili. The company is obviously not contented with being an ACG-only hub on its way to let “everyone find the content they like and the friends who share common interests.” Bilibili will also need to prove user growth and revenues if its IPO rumor materializes. The user registration quiz has already gotten easier and shorter—there used to be 100 questions. The site currently makes money from selling paid subscriptions, imported and self-made games, as well as ACG merchandise. It declined to comment on its profitability.

“I used to devote all my weekends to Bilibili, incessantly refreshing the homepage for new video uploads, not just anime episodes, but all the stuff that we ACG fans like. But I don’t use it as often now,” says Phillip Yuan, a 24-year-old graduate student at Shenzhen University. “It’s changed a lot through the years. Now you see a lot of non-ACG stuff.”

The danmu and UGC phenomenon that has let youth participation bloom and Bilibili thrive is also looking rocky. Any form of restriction on original content will hamper user interaction and video mashup production, Tang suggests.

“I think the major impact of the regulation is that it will scare many users who tend to think Bilibili and other subcultural sites are not their safe space anymore,” Yin echoes that sentiment, though expressing some cautious optimism. “The video industry, as well as ACG industry, are still commercially significant so that the restriction itself is negotiated with capital as well. There is still room for related youth practices and consumptions to carry on.”

–This article originally appeared on TechNode.