Written by Yiu-wai Chu.

Written by Yiu-wai Chu.

Billed as the film to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong production company Milkyway Image, action film Three (2016) marks the return of director Johnnie To to his signature gangster movie after Drug War (2013), the first gangster film he shot entirely in Mainland China. The famous director and the company he co-founded in 1996 are walking a fine line between Mainland China and Hong Kong: For staunch supporters of To and Milkyway Image, his unexpected interim project, the stage-to-screen musical Office(2015), had just been another Mainland movie in order to “walk with two legs”: using commercial films such as rom-com Don’t Go Breaking My Heart (2011) to support the production company’s unique brand of “action thriller meets art-house cinema.” Two years earlier, his 50th film Drug War had seen mixed reviews in Hong Kong. I have argued elsewhere that this was due “the untranslatability of Milkyway-cum-Hong Kong flavour that distinguished To from other Hong Kong directors, who were assimilated into the Mainland market as a simple mélange.” Straddling their home turf and the highly profitable Mainland market, To and Milkyway Image may be emblematic of challenges faced by Hong Kong cinema more widely – and of ways to tackle them.

In this light, how is To’s most recent film, Three, to be seen? Shortly before its premiere in Hong Kong, an article entitled “Johnnie To: Going Deep into the Tiger Mountain” discussed the successes and losses of the director’s endeavors since his first co-production project Don’t Go Breaking My Heart in 2011. Taking the bull by the horns, To went deep into the Mainland market, undeterred by the “tigers” there. However, his tiger mountain venture seems not as spectacular as previous experiments in his famously stylistic gangster noir films. While Three is recognized by film critics as another project of To’s exceedingly aesthetic experiment with among other things manual slow-motion, it was not particularly well received by To’s fans in Hong Kong. As written recently in the New York Times, “The elaborate, largely slow-motion multifloor action climax is as audacious as anything he has staged and filmed… [but the] movie offers little resonance beyond that; it’s not a career highlight for the director”. Some fans would even argue that the film was “castrated,” and thus failed to present the real Johnnie To.

Be that as it may, I would argue that the northern expedition of Johnnie To has to be read alongside the inheritance of his company Milkyway Image, which To made clear in an interview during the “Udine 2016: Far East Film Festival”: “Milkyway these years has been training new people, hoping to continue, but I do not want to interfere too much. Milkyway Image’s future should be decided by a new generation.” To knows very well that the future of Milkyway Image – and even Hong Kong cinema per se – does not lie in the Mainland market.

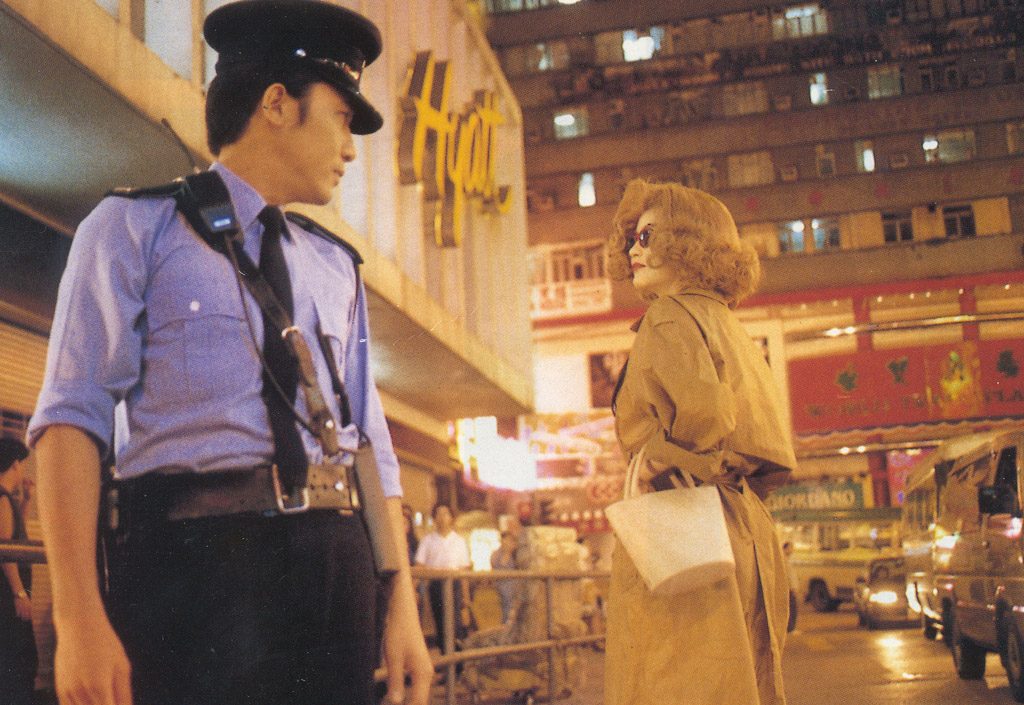

It is important to note that Milkyway Image has been walking with two legs nevertheless: Motorway (2012) directed by Pou-soi Cheang, highlights the importance of inheritance and transmission in the film sector through the mentor-mentee relationship between the actors Anthony Wong and Shawn Yue. After his successful Milkyway Image projects, Cheang hazarded north to produce blockbusters such as The Monkey King (2014) and The Monkey King 2 (2016).

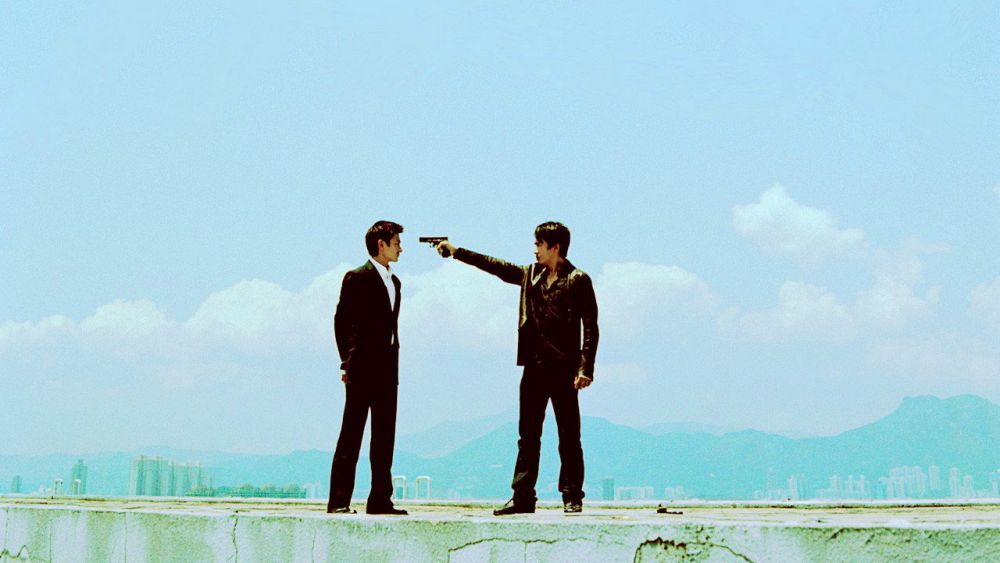

Meanwhile, Milkyway Image’s inheritance is alive and well on home soil: In April 2016, Trivisa, an action crime thriller directed by three new directors – Frank Hui, Jevons Au and Vicky Wong – was released by Milkway Image in Hong Kong. Produced by Johnnie To and his long-time collaborator Patrick Yau, the typically “Milkyway Image” film adapts the stories of three real-life notorious mobsters before Hong Kong’s reversion to China in 1997. The three rookie directors were handpicked through Hong Kong’s “Fresh Wave” Short Film Competition, which was masterminded by To. The fact that Trivisa opened the 40th Hong Kong International Film Festival in March 2016 and had its world premiere at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival’s Forum section spoke volumes about its significance. Many fans of Milkyway Image and Hong Kong cinema shared reviewer Martin Sandison’s feeling: “Coming out of the film I was overcome with feelings I have experienced many times before with Hong Kong cinema: euphoria, glee and passion.”

Not unlike Drug War or Three, Johnnie To was reportedly planning to screen Trivisa in Mainland China, but in the end decided to keep it to the local Hong Kong market as his team did not want to compromise between their artistic interest and Mainland censorship. Bookended by news footage from 1997, the film alludes to the return of Hong Kong under Chinese control, corruption of Mainland officials and the disappearance of Hong Kong. It ends with “Let It Be Gone with the Wind,” a Cantopop oldie originally sung by Hong Kong veteran singer Kenny Bee in 1987.

Recent Hong Kong directors tend to have a special liking for Cantopop oldies such as this one: The use of Cantopop “Wind and Cloud” (originally sung by Sandra Lang in 1979) and “You’re the Best in the World” (originally sung by Roman Tam and Jenny Tseng in 1983) as theme songs in Alan Mak and Felix Chong’s Overheard 3 (2014) and Stephen Chow’s The Mermaid (2016) respectively are two recent examples. Much more than summoning up memories of the good old days, the song “Let It Be Gone with the Wind” perfectly fits the theme of Trivisa with a lingering taste of sorrow with overtones of destiny: “Like the north wind, you blew my dreams away; let everything be gone with the wind.”

Ironically enough, 1997 proved to have changed not only the fate of the three mobsters but also that of the former British colony forever. But the spectacular debut of the three first-time directors shows that some of its inhabitants simply refuse to let it be gone with the wind. As written by Edmund Lee in the Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post: “If Trivisa is any indication of the bigger picture, Hong Kong cinema’s future may be a lot brighter than that of the city itself.” Owing to the stellar rise of China, Hong Kong and its cinema have recently been seen by many as dying. The intertwined narratives of the mobsters in the film may signal the end of an era, but thanks to the uncompromising effort of Hong Kong filmmakers, we will witness the dawn of a new one – at least for Hong Kong cinema.

-This article originally appeared on China Policy Institute