Shorter-form Video and Livestreaming

Around 2016, things really started looking down for Youku as viewers’ attention spans started to split into other forms of video. In 2016, what was now Youku Tudou lost $250 million (RMB 1.7 billion), as users started to turn to platforms like Miaopai, Meipai, and livestreaming platforms like Yizhibo.

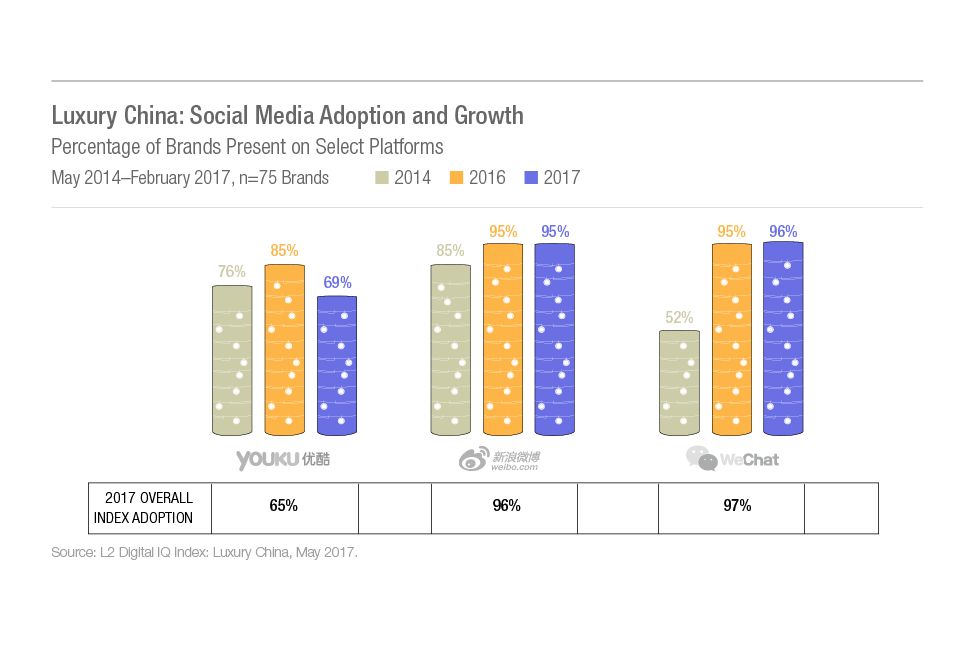

In 2017, according to L2, Miaopai videos featuring luxury watch and jewelry brands saw an average of 73,700 more views than comparable videos on Youku, with fashion brand videos seeing nearly double that. Livestreaming also quickly grew in popularity — that year livestreaming attracted nearly half of China’s internet users.

For Chinese long-form video content creators, these newer platforms also had an added monetization bonus, allowing digital “red envelopes” or monetary gifts from viewers, which further incentivized KOLs to create content that would really appeal to the user.

Though, long-form video platforms have been competing for both audiences and content creators and as new regulations further shaped the video landscape, long-form video never completely went away. Weibo’s adoption of social video that allows for user-generated long-form content (through hosting links to Miaopai, Youku, and other platforms) is considered one of the only spaces where it thrives. In fact, many credited videos to Weibo’s comeback under WeChat’s shadow, as it now has blossomed into a platform that supports a wide variety of content mediums, from long-form video, to short-form, to live-streaming, to full articles. In December 2018, Weibo moved deeper into this space when it officially started allowing Chinese long-form video content creators to upload 1080p HD video.

The Case for Chinese Long-form Video Content Creators

“There’s definitely still life in long-form video,” says Whaley. “It’s more searchable and appealing if you want to learn something or have a fuller experience with a content creator.”

Simply put, those on the supporting side of the long-form video debate agree that a lengthy video allows content creators to tell a better, persuasive story and makes more time for the brand or KOL to create an emotional bond with the audience. A 2016 ad study from Google, for instance, suggests that different lengths of video can serve different purposes, with shorter video ads better for brand awareness and longer ones better for brand favorability.

Long-form’s success as a content medium ultimately comes down to a variety of factors, including how long the video is, what platform it’s on (Hootsuite suggests attention spans vary on different platforms and depending on the setting) and just how creative the content gets itself. This is true in marketing even if video isn’t involved: to illustrate, in 2017, the same year Chinese viewers’ attention spans seemed to be getting shorter, one digital marketing trend managed to keep viewers captivated for ages — that is, with an endless feed of illustrations that tell an engaging story. Only after a user scrolled on their phone to the very end of the strip would the brand’s message be revealed.

Production quality is also a factor — just as it was for Youku back in 2009. Weibo vloggers who have grown an audience with long videos featuring interviews, tutorials, and even style shoots, are putting in the time to create high-quality visuals. This fashion vlogger on Bilibili and Weibo shoots outfit try-ons and beauty demonstrations in her living room, but creative camera-work and editing make her 12 to 14-minute videos more polished for audiences.

Meanwhile, the growing influence of Bilibili over a coveted market, China’s Gen-Z consumers, who have a particular penchant for making purchases through social media, isn’t going unnoticed.

“The reality is Chinese long-form video content creators never died, they just changed and they will continue to change,” Whaley says. “Absolutely 100 percent there’s still demand long-form. It offers a value proposition that no other type of content can.”

– This article originally appeared on ParkLu Blog and has been republished with permission.