One of Lu Benwei’s old videos on Weibo, accessed on April 12, 2019. Lu was banned from all video and live-streaming platforms after insulting another content creator and creating a ‘very bad social influence’ in 2017. (Image credit: TechNode/Eugene Tang)

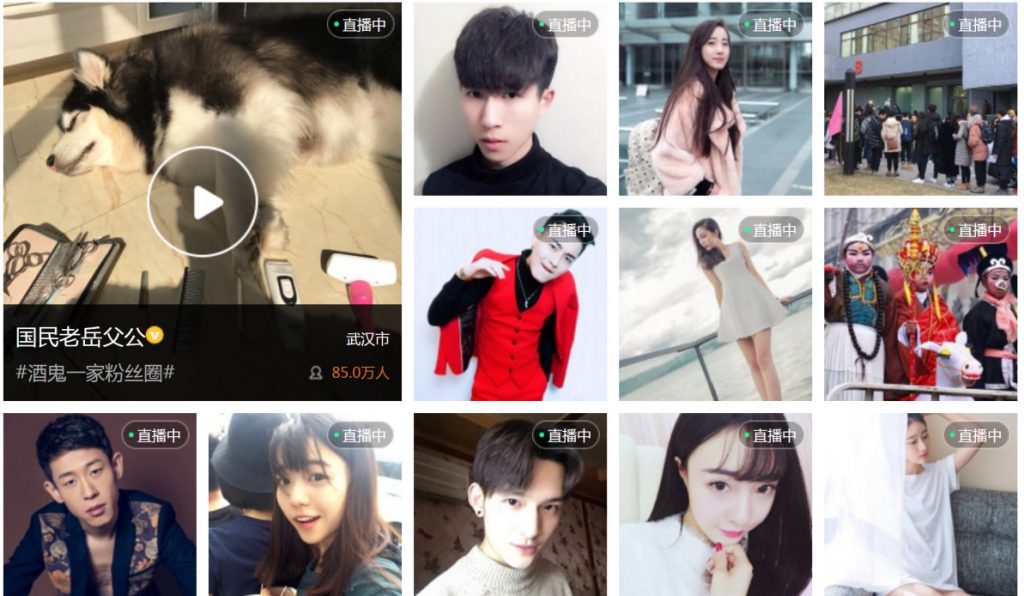

Pay close attention to China’s live-streaming scene, and you’ll notice that several stars vanished in 2018, leaving no trace on the platforms where they used to perform.

The reason for their disappearance is by no means mysterious—they either said or did the “wrong” things and were banned. This was the case for four of China’s most popular and highest-grossing live-streaming celebrities: Li Tianyou, Lu Benwei, Chen Yifa, and Yang Kaili.

Banned either directly by the country’s top internet content regulator, the Cyber Administration of China (CAC), or by their respective platforms in 2018, the four live-streamers were emblematic of the wild and largely unregulated growth the country’s live-streaming industry once enjoyed but probably not see again.

On April 9, the CAC was tasked by the National Office Against Pornographic and Illegal Publications (NOAPIP) to carry out an eight-month internet cleanup campaign of noncompliant content on various platforms. In an announcement issued the same day, NOAPIP reiterated the rules for self-regulation, which require private companies to identify and remove content deemed unacceptable by content regulators.

Prior to 2018, such rules were only loosely followed by live-streaming and short-video platforms, and primarily targeted illicit content such as pornography.

However, starting last year, the CAC and NOAPIP significantly increased pressure on these platforms to conduct self-regulation, with special emphasis on vulgar but not necessarily illegal content. For example, pranks and excessive swearing, though not illegal, were now considered unacceptable.

In 2017, the CAC and NOAPIP carried out only one cleanup campaign, which shut down 18 live-streaming platforms that contained sexually explicit content. Just one year later, their stance had hardened. In addition to summoning the executives of 21 platforms such as YY, Douyu, Huya, and Kuaishou, the two authorities also carried out two cleanup campaigns that shut down more than 5,000 live-streaming channels, and issued a set of stringent guidelines for the platforms.

The aforementioned four live-streamers were caught up in this sweep. Despite their popularity and profuse apologies, they were promptly banished from the industry.

Rise to Fame

Li Tianyou, 25, is a tall and skinny man from Jinzhou, a city in northeastern China’s Liaoning province. He started his online career in November 2014 on YY, the live-streaming platform and parent company of New York-listed Huya. He gained the spotlight with several hit rap songs whose lyrics dwelt on the bitterness of relationships. Soon, he had more than 20 million subscribers on YY and over 40 million followers on short-video platform Kuaishou. Li occasionally stepped out of the live-streaming booth to star in variety show broadcasts and movies.

Lu Benwei, 27, is a gamer known for his thick mop of hair. His followers affectionately call him wu wu kai, or “50/50,” because he once boasted of having a 50/50 chance of winning a tournament, only to be hilariously torpedoed by three losses in a row.

Lu started off as a professional player of “League of Legends” in 2011, and competed for a team named “Royal” for three years. After he won second place in the game’s Season 3 World Championship in 2013, he started live-streaming on Douyu, one of the largest live-streaming platforms in China.

Lu’s gaming skills and foul-mouthed style, which appealed to young viewers, helped him amass more than 13 million subscribers on Douyu, and more than 7 million followers on Weibo by the end of 2017.

Formerly a graphics designer in Chongqing, Chen Yifa, 33, started live-streaming on Douyu in September 2014. She soon gained popularity for her genuine persona, standup comedy style, and singing skills, becoming one of the top live-streamers on the platform. Chen made inroads into the music industry; in 2016, her song “Fairy Town” ranked #5 on NetEase’s Top 100 song chart. According to media outlet The Paper, Chen had more than 11 million subscribers on her Douyu channel before she was banned.

Yang Kaili, 22, had the fastest rise to fame. Known better as “Lige,” her popularity surged on short-video platform Douyin in June of last year on the back of a hit song. In the ensuing four months, before her account was banned, the number of her followers on Douyin rocketed to 44 million. After being signed by Huya in September 2018, she gained 2 million subscribers in a month.

Abrupt Downfall

An advisory on Douyin from April 12, 2019 advocates for ‘healthy’ live-streaming. Douyin bans content that is political and sexual in nature, and live-streamers found guilty could have their accounts banned permanently. (Image credit: TechNode/Eugene Tang)

While it took years—or months, in the case of Yang Kaili—for these live-streamers to reach the top tier of their respective platforms, it only took a few incidents to reduce their careers to tatters.

Li Tianyou’s downfall was deeply embedded in his rap lyrics and the lifestyle that he promotes in his shows. Several of his now-banned songs praised methamphetamine, calling the illicit drug “wonderful” and capable of “erasing all worries” (our translation), and describing in detail the sensation of being high on meth. Li’s livestreams also featured extravagant displays of wealth, including stacks of cash, luxury watches, and expensive sports cars.

As part of a crackdown in February 2018, Li was singled out by the CAC in an announcement for spreading narcotics-related music, flaunting his wealth, and posting lowbrow content. The announcement ordered all live-streaming and video platforms to ban Li and prevent him from registering other accounts, calling his behavior “a blatant violation of public order and good customs” that “corrupts social customs and damages the physical and mental health of youths” (our translation).

As for Lu Benwei, profanity eventually became his undoing. After being accused of using cheats when live-streaming a game in November 2017, Lu vehemently defended himself on his channel, insulting the content creator who made the accusation and instigating fans to verbally abuse him.

Netizens were appalled by Lu’s malicious remarks and soon pressured the star live-streamer to apologize, which he did in December 2017 on his Weibo account. In January 2018, Douyu temporarily suspended his channel and fined him RMB 1 million (around $148,810) for the “very bad social influence” of his actions. That wasn’t enough for CAC, which subsequently banned him from all video and live-streaming platforms in the same announcement that cemented Li’s downfall.

While Li and Lu consistently behaved in an “noncompliant” fashion, Chen Yifa’s offense stemmed from a single live-streaming session in 2016. According to a widely circulated video, Chen made joking mention of historical events such as the Nanjing Massacre and Japan’s occupation of northeast China. She also described a game character’s movement as honoring the Yasukuni Shrine, a Shinto shrine in Tokyo whose commemoration of war criminals from World War II is considered particularly offensive to many Chinese people.

The footage was quickly picked up by the internet police of east China’s Jiangsu province and subsequently by China Central Television Station. Douyu swiftly suspended Chen’s channel in July 2018 and pledged to expand its content-filtering team. However, Chen’s popularity did not die down even during her suspension, as the chat and tipping functions on her channel were still accessible. On Sept. 11, 2018, fans eager to celebrate Chen’s fourth year on Douyu sent her more than RMB 220,000 worth of gifts and more than 800 messages that wished for her early return, according to media outlet The Paper.

Douyu released a statement in October 2018, apologizing for what it called “a gross lack of awareness in social responsibility, platform management and security” and completely shut down Chen’s already suspended channel. Chen’s Weibo account was also revoked around the same time.

While the historical events Chen mentioned are not wholly taboo, referring to them with the wrong tone could still incur problems, said Sarah Cook, a senior researcher at watchdog organization Freedom House. “For some historical events like that, simply mentioning them may not be a problem, but the way they are mentioned or the narrative given could be the issue … Any effort to depart from the official narrative when discussing the event could cause problems for someone,” said Cook.

Yang Kaili, or “Lige,” was the only one of the four banned live-streamers to have broken the law. During a live-streaming show on Huya in October 2018, Yang was seen singing China’s national anthem, “March of the Volunteers,” in a jovial tone while waving her arms like an orchestra conductor. Huya immediately blocked Yang’s account, took all of her videos offline, and issued a statement saying that Yang lacked awareness of “law and social responsibility.”

According to a national anthem law introduced in 2017, public performances of the song that involve intentional changes to the lyrics and melody, as well as any distortion or disrespect to the song, are punishable with up to three years in prison, depending on the severity of the violation.

Yang responded quickly with two apologies on Weibo, acknowledging her actions as “stupid and ‘low-level’ mistakes” and promising to stop all live-streaming activities to “fully accept ideological-political education and patriotic education” (our translation). Despite the apologies, Yang was still detained by Shanghai police for five days, according to a Weibo post from the police department.

Self-regulation

The CAC references three sets of regulations when punishing live-streaming platforms and live-streamers: China Internet Security Law, Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services, and Administrative Provisions on Internet Live-streaming Services. While the rules are adamant about the prohibition of illegal content such as pornography, they gloss over what types of non-illegal content count as a violation. The Administrative Provisions on Internet Live-streaming Services, for instance, requires platforms to cultivate a “positive and healthy atmosphere” for users but do not specify what is deemed “negative” or “unhealthy.”

“China’s content regulations are written in a vague and broadly defined fashion on purpose,” said Lotus Ruan, a researcher at the Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto, an interdisciplinary laboratory that studies information controls. “Private companies and users are left to guesstimate what the taboos are and you rarely know for sure where the red line is until you cross it.”

This was the case for the four ousted live-streamers, whose offenses were the first of their kind to be deemed unacceptable by the CAC or other content regulators such as regional net police.

The absence of detailed guidelines from content regulators has forced private companies to step up their self-regulation game. Huya, for instance, has released 15 sets of rules or updates of existing rules to control different kinds of content since the beginning of 2018. During the same period, Douyu released eight new sets of regulations.

Some of those rules go into minute detail. Huya’s regulations on the genre of ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response), which is sometimes used as a guise for sexually suggestive content, prohibit “putting legs in front of the camera,” 11 categories of clothing, and “objects that could be used for producing lowbrow content,” such as bananas, jelly, and lollipops.

Another set of regulations from Huya pledges to “regularly organize patriotic education sessions for live-streamers,” which involves “visiting red education bases”—a reference to facilities that teach the history and theory of the Communist Party of China—and “learning the heroic deeds of past heroes and martyrs.”

According to Ruan, the burden of self-regulation has been pushed further down to individual users in recent years. “We see that in some cases not only live-streaming platforms are punished for failing to censor unwanted content, but individual users are also held responsible for producing or sharing that content,” she said.

Some popular live-streamers are visibly trying to appease content regulators both in their shows and on social media. One of Douyu’s most valued live-streamers, Liu Mou, better known as “PDD,” also had a reputation for using salty language. Based on TechNode’s observations, however, while Liu still occasionally uses profanity in his recent livestreams, the frequency is much lower as compared to a few years ago, and tends to be the milder type used for emphasis.

Another live-streamer on Douyu, Feng Yanan, known online as “Feng Timo,” carries out self-censorship on Weibo. Since May 2018, the live-streamer, who has 19 million subscribers on Douyu, has been reposting content from the official Weibo accounts of the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League and the state media People’s Daily that promote positivity or commemorate important dates or events. Starting from March, she has increased the frequency of reposts from the People’s Daily to every day, adding comments to each repost.

Even those who have been banned appear to be following suit. Lu, for instance, has resumed use of his Weibo account, which had sat abandoned since his apologies of December 2017. He reposts from the official accounts of the People’s Daily and the Central Commission for Guiding Cultural and Ethical Progress.

Lu recently reposted an announcement from NOAPIP, the pornography and illegal content watchdog, that called on platforms and regulators to further crack down on noncompliant content.