A stick used against South Korea could become a carrot for Hollywood as China looks to improve trade ties with the US.

Allowing more Hollywood movies onto cinema screens would be an easy way for China to demonstrate goodwill towards the United States and is therefore likely, a Chinese researcher told the South China Morning Post Wednesday.

Just as China has been using restrictions on South Korean entertainment imports as a stick to express its displeasure over that country’s preparations to deploy an American defensive missile system, permitting more Hollywood films to be imported on a revenue-sharing basis would be an easily-deployed carrot to offer the United States, as the two sides seek to improve commercial ties after their presidents met in the US last week.

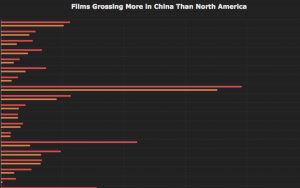

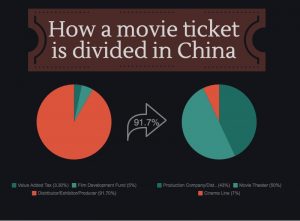

China currently allows 34 non-co-production films to be imported annually, on a revenue-sharing basis. Increasing Hollywood movies would likely mean an overall increase in the number of total imports, otherwise the import quota would become a zero-sum game, with the American industry’s gain becoming another nation or nation’s loss.

Allowing more Hollywood films, along with other moves including increased purchases of US natural resource products, are visible and easy choices China can make that also look like clear wins for US President Donald Trump, said Mei Xinyu, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, in the South China Morning Post interview.

China and the United States currently have a US$347 billion trade imbalance, with the US on the losing end of it, due in large part to the number of goods manufactured in China that are then sold to American consumers.

However, letting in more Hollywood movies is no guarantee of their performance. In 2016, instead of officially changing the 34-film quota, China allowed six additional imported films at the end of the year — all of them American films — but only one of the six, Hacksaw Ridge, was a break-out hit. In some cases, films like Legendary’s Warcraft have performed poorly in North America but were hits in China. More likely than an official policy would be a continuation of the 2016 experiment; that is, the number 34 would remain, but Chinese policymakers could allow more films — from not just the US but also other nations — as it sees fit, based on market and political conditions.

And all of that depends on box office performance. China is now the world’s number two film market, slow growth in 2016 means it will be a while before it tops the United States. Overall ticket sales have been lackluster so far this year, although this weekend’s release of The Fate of the Furious, the next installment of the China box office champion The Fast and the Furious series, could begin to grease revenue wheels as summer approaches.