China Literature has been betting big on selling adaptation rights to novels or comic books published on its platform to filmmakers, TV producers or game developers.

China Literature Limited Co-Chief Executive Officers Liang Xiaodong (R) and Wu wenhui (L) hit a gong to launch the companies Intial Public Offering at the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on November 8, 2017.

Shares in Chinese internet giant Tencent’s e-book arm, China Literature, surged more than 60 percent on their debut on the Hong Kong stock exchange, after raising 1.1 billion USD in an IPO. / AFP PHOTO / ISAAC LAWRENCE

Romance, mystery, and martial arts — these are some of the most important ingredients that went into one of the year’s biggest initial public offerings (IPOs) of a Chinese technology company.

China Literature, web entertainment leader Tencent’s online publishing unit, saw its share price double on its first day of trading in Hong Kong on Nov. 8 after an immensely oversubscribed IPO that raised HK$8.33 billion ($1.07 billion).

The company, which was formed in a 2015 merger between Tencent Literature and Shanghai-based Shanda Cloudary, operates an online book marketplace similar to Amazon’s Kindle Store, as well as an e-reader service accessible through Tencent’s WeChat messaging app.

Some of China Literature’s e-books are free-to-read for the first few chapters, but users who get hooked must pay a fee to keep reading — a major source of revenue for the company.

China Literature has also been betting big on selling adaptation rights to novels or comic books published on its platform to filmmakers, TV producers or game developers. The Chinese film “So Young,” for example, premiered in 2013 after being adapted from the college romance novel “To Our Youth That Is Fading Away.”

The company recently signed lucrative deals with local video streaming sites seeking to adapt its hit manga series “Fights Break Spheres” and “The King’s Avatar.” Such deals not only help generate income for China Literature through licensing fees. Content adaptors will also share revenue from ads embedded in the TV series and selling animation merchandise.

Chinese investors’ appetite for purchasing intellectual property (IP) for adaptation has been growing since 2015. But the amount spent acquiring IP remains far lower than in developed markets. For example, adaptation rights fees account for about 5-10% of the total cost of production in Europe or the U.S., while the figure is less than 5% in China. Several adaptations have also done poorly at the Chinese box office or failed to covert online readers into viewers, casting doubt about the viability of this approach.

China Literature Co-CEOs Liang Xiaodong (right) and Wu Wenhui (left) raise glasses of champagne at the company’s initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on Nov. 8. Photo: Visual China

Recently, Caixin spoke to China Literature’s Co-CEO Wu Wenhui, who has been in the online literature industry for more than 14 years. Here are translated excerpts from the Chinese-language interview.

Caixin: You’ve held onto your goal of listing the business, which you had even when it was still Shanda Cloudary. You’ve now completed an IPO. What do you think is different about a listing now, compared to in the past, before your merger with Tencent?

Wu: Now, the market has a clearer view of China Literature’s business model. Whether it’s the e-book business or the intellectual property business, they all have a place in the future of the cultural industry. Everyone looks more favorably on China Literature — that’s the difference between the present and the past.

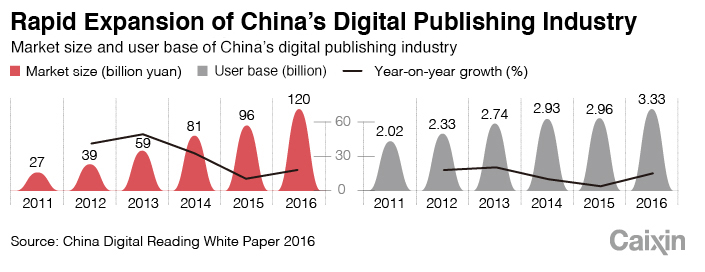

Looking back, which business strategies or changes have had the biggest impact on China Literature becoming the “top dog” of online literature?

The electronic payment business model that started in 2003 quickly put the entire online literature industry on track to commercialization. At the same time, it helped the industry amass a large volume of content and users within a very short period of time. In 2013, wireless internet helped promote a further expansion of the user base, and the industry developed even faster. Starting in 2015, intellectual property adaptations (such as films and games based on online novels) caused the business to grow even more. It became widely recognized that intellectual property had very high adaptation value. This caused everyone to have even bigger expectations for online literature.

Are rampant piracy and downstream companies developing their own intellectual property serious threats to China Literature’s main business?

If you look at the e-reading side of the business, there is indeed a lot of piracy, but we are continuously improving China’s publishing environment. Starting with last year’s “Sword Net” campaign (launched by the National Copyright Administration), legal measures have been continuously strengthened, and this kind of improvement is long-lasting.

On the intellectual property side, everyone is becoming more mature and rational in the way they look at the use of intellectual property. They are focusing more on packaging intellectual property. This is a benign trend for the development of the intellectual property industry. From this angle, intellectual property’s value to China Literature isn’t in terms of quantity, but more so in terms of deeply developing high-quality intellectual property products. I believe China Literature’s content has its appeal.

One of China Literature’s strengths, according to the company, is that it offers high-quality content at lower fees. In the current climate where online platforms engage in bidding wars over authors, can this model continue?

Any action is rational business behavior — as an online literature platform with a market advantage, China Literature can help authors publicize their work, help them to sell their work at a very good price for intellectual property to those who want to adapt it into film, television show or game. We cooperate with authors in a mutually beneficial way. As for other companies’ method of using high prices to attract big names, we think this is short-sighted, unsustainable behavior. Companies like us, who have been in the industry for 15 years and have a long-term vision, we are willing to use long-term methods to cooperate with authors… additionally, we have a good team and content platform experience, and are able to continuously find new, young authors.

What are some of the details about your long-term intellectual property cooperation with authors?

A good adaptation of intellectual property happens on many levels. At the moment, one piece of intellectual property can be turned into a film, a television show, a game, a car, and many other types of adaptations. For instance, after translation, it can be published overseas. There are numerous models for development. If the product doesn’t have a good strategy — it’s possible this product will only be used once — the adapted productions could be of shoddy quality. We can see a lot of intellectual property in Europe and the U.S. with continued, long-term development. As an experienced platform, China Literature wants to provide authors’ intellectual property with prolonged publicity, packaging and cultivation.

Objectively speaking, it’s rare to see good intellectual property being successfully adapted into good movies and games. Why is this the case? And, faced with this reality, is China Literature’s intellectual property business sustainable?

The main reason is that China’s cultural industry is still young. This includes intellectual property development, the film industry, and so on, which still have some way to go before they reach international standards. Thus, our success rate when we adapt intellectual property products isn’t that high. But if you look at the mature markets in Europe and North America, many of their best film productions originate from existing intellectual property (like comic books or novels). From this point of view, China might still need some time to learn, and catch up with mature business models.

I believe demand for intellectual property from China’s cultural industry will always be extremely high, but whether it will be used and adapted well will depend on a process of recognition and improvement.

– This article originally appeared on Caixin Global.