Every day while CFI’s Hollywood readers take in the business of the Chinese film industry, the actual movies can sometimes seem exotic or remote. But in major US cities, mainstream Chinese films are increasingly available: thanks to Wanda’s purchase of AMC and distributors like China Lion, they get American theatrical releases practically simultaneous to their premieres at home. Though they receive virtually no publicity outside the non-Chinese community, these films are more than worth seeking out by anyone serious about engaging the Chinese industry, understanding the Chinese sensibility and familiarizing themselves with China’s talent pool. Periodically, CFI will review and point readers in the direction of noteworthy US releases of contemporary commercial and independent Chinese titles.

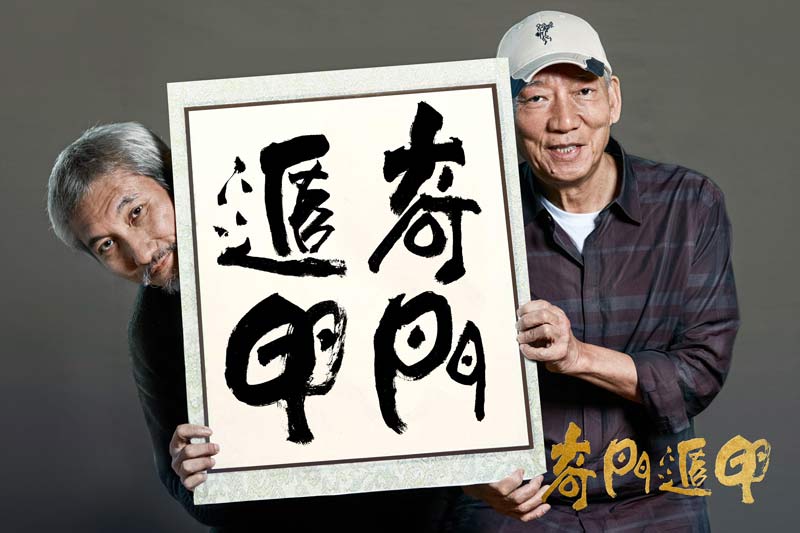

Warriors battle demons who threaten Earth in an effects-laden fantasy from Hong Kong legends Yuen Wo Ping and Tsui Hark.

Either a daring effort to visualize an ancient ethos or a brazen cashing in on the special-effects craze sweeping the Asian movie industry, The Thousand Faces of Dunjia is first and foremost a Tsui Hark joint. If you like his style of dense plotting, mysterioso set-pieces and weird sex, Dunjia is a blast—but with a lot of holes in it.

The movie, co-written, co-produced and co-edited by Hark, takes off from Qimen Dunjia, shown as a frankly baffling form of divination whose secret, horoscope-like codes give its practitioners superpowers. Like Hark’s 1993 movie Green Snake, which turned a Buddhist creation story into a sex romp that destroys the world, Dunjia explains its theory of divination in terms of a band of martial-arts heroes who fall in and out of love while battling CG enemies.

In some ways The Thousand Faces of Dunjia is like an unauthorized remake of Stephen Chow‘s Journey to the West, which put Buddha into a Warner Bros. cartoon. (Hark directed a much-less-successful sequel.) There are the same slapstick transformations, the same lethal but tenderhearted heroines, the same physical mutilations—only with a greater emphasis on edgy sex. Lovers here slap each other silly as foreplay, and are constantly angling for threesomes with demons.

You’ll like Dunjia if, in your world view, well-meaning but none-too-bright tough guys get taken advantage of by beautiful but scheming women, many of them actually demons. Or if you find it plausible that a disorder in the cosmos has permitted aliens to stride hidden across the Earth, looking for magic weapons to destroy something or other.

What’s missing is an emotional or intellectual core, a sense of an inward journey to enlightenment. The themes here don’t progress much beyond a fundamental battle between yin and yang, seen as water and fire demons duking it out in the skies.

What you won’t find in Dunjia is the kind of action that made director Yuen Wo Ping such a revered name in martial-arts circles. Since his work on Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and The Matrix trilogy, Yuen has put together elaborate choreography in stunt-heavy movies like The Grandmaster and Ip Man 3.

The few fights in Dunjia consist almost solely of mediocre CG beings—like a red hairball with wings or a bat thing with fangs—throwing fireballs at each other. Like Japanese kaiju movies from 60 years ago, and sci-fi cliffhanging serials before that, Dunjia has a certain boyish charm, an adolescent “gee whiz” tone that is hard to resist but just as hard to warm up to.

Like a lot of Hark’s movies, the most appealing moments in Dunjia are when the characters sit down and wonder why the people they love treat them so poorly. Dragonfly, a Shu Qi-like warrior played by the marvelous Ni Ni, can’t understand why her boyfriend Zhuge (Da Peng) keeps ending up in the arms of a naked Xiao Yuan (award-winning gamin Dongyu Zhou, star of Soul Mate and This Is Not What I Expected). Or why she’s so drawn to bodybuilder and idiot cop Dao Yichang (Aarif Lee from Kung Fu Yoga). Their screwball pangs might have made a more interesting, or at least more mature, movie.

— This article originally appeared on Film Journal.

WHAT DOES THE GRADE MEAN?

Here are some recent & modern-era vintage Chinese and Hong Kong films for comparison

- A+

- PLATFORM (2000, dir Jia Zhangke)

- THE WORLD (2004, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- DRUNKEN MASTER 2 (1994, dir. Lau Kar Leung & Jackie Chan)

- KUNG FU HUSTLE (2004, dir. Stephen Chow)

- A

- LET THE BULLETS FLY (2010, dir Jiang Wen)

- THE MERMAID (2016, dir. Stephen Chow)

- A TOUCH OF SIN (2013, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- STILL LIFE (2006, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (2015, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- LITTLE BIG SOLDIER (2010, dir. Ding Sheng)

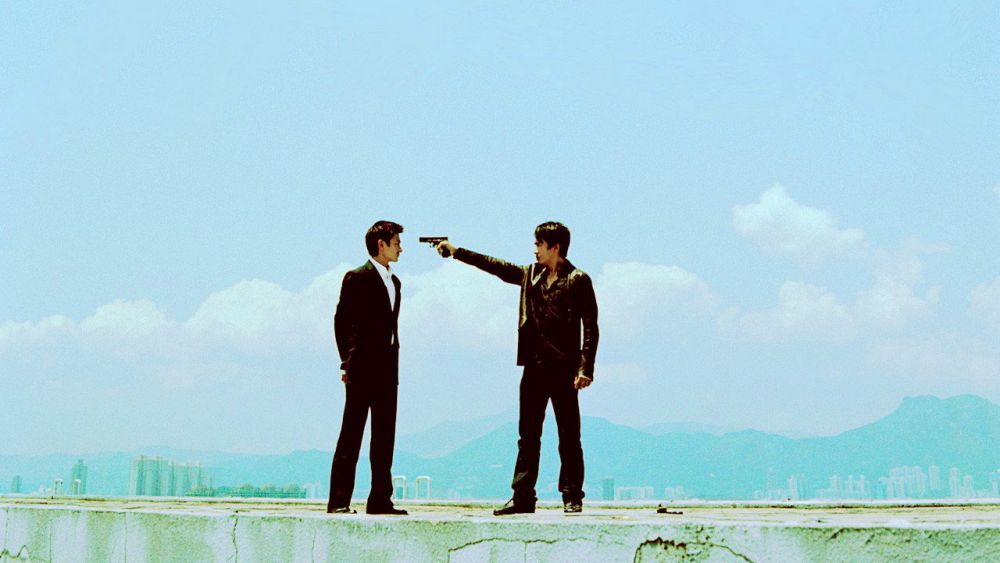

- EXTRAORDINARY MISSION (2017, dir. Alan Mak & Anthony Pun)

- MR SIX (2015, dir. Guan Hu)

- A WORLD WITHOUT THIEVES (2004, dir. Feng Xiaogang)

- SUZHOU RIVER (1999, dir. Lou Ye)

- HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS (2004, dir Zhang Yimou)

- RAISE THE RED LANTERN (1991, dir. Zhang Yimou)

- A-

- DUCKWEED (2017, dir. Han Han)

- I BELONGED TO YOU (2016, dir. Zhang Yibai)

- B+

- THE GREAT WALL (2016, dir. Zhang Yimou)

- OLD STONE (2016, dir. Johnny Ma)

- CRAZY STONE (2006, dir. Ning Hao)

- GO, LALA GO (2010, dir. Xu Jinglei)

- B

- KUNG FU YOGA (2017, dir. Stanley Tong)

- RAILROAD TIGERS (2016, dir. Ding Sheng)

- THE WASTED TIMES (2016, dir. Cheng Er)

- CHONGQING HOT POT (2016, dir. Yang Qing)

- MONSTER HUNT (2015, dir. Raman Hui)

- B-

- JOURNEY TO THE WEST: THE DEMONS STRIKE BACK (2017, dir. Tsui Hark)

- SOME LIKE IT HOT (2017, dir. Song Xiaofei & Dong Xu)

- BORN IN CHINA (2016, dir. Lu Chuan)

- D-

- TINY TIMES (2013, dir. Guo Jingming)