China Hollywood Society’s Executive Director doesn’t want to make cross-cultural megabudget blockbusters, but she’s happy to help you with yours.

Welcome to China Film Insiders, a ongoing series featuring significant creators, producers, funders and behind-the-scenes members of the ever-expanding China-Hollywood entertainment universe.

In 2012, the Canadian-Chinese producer and screenwriter Melanie Ansley was a grad student learning the ways of Hollywood at USC’s prestigious, industry-feeding Peter Stark Producing Program. But she also found she was meeting a growing number of filmmakers like herself: enterprising bicultural, bilingual people engaged in projects that had them shuttling back and forth between Los Angeles and Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, all hoping to build bridges and take advantage of new opportunities being created by the efflorescence of China’s film scene. Looking to foster a sense of mutual aid, a couple of Ansley’s grad school colleagues launched the China Hollywood Society to provide resources, support and networking opportunities for this burgeoning community.

Last year, Ansley, who grew up in Shanghai and lived in Beijing for seven years as an adult, became Executive Director of the China Hollywood Society. With a membership close to five hundred working professionals, the group arranges networking events, and actively promotes best practices and connections to jobs on films in the planning stage. The Society is advised by veteran producers Janet Yang and Michael Andreen; by Chris Fenton of the Beijing-based studio DMG; and by blogger-producer, Robert Cain.

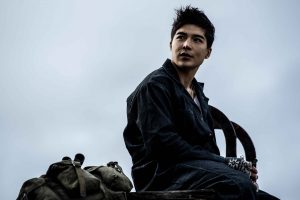

This week, in advance of the Tribeca Film Festival premiere of her Chinese-language comedy, King of Peking, Ansley spoke to China Film Insider. While the film and Ansley’s sensibility are both strongly indie, Ansley’s USC training makes her more than conversant in studio thinking, and has put her in the mix with the current generation of mainstream executives and producers—in short, she’s someone to keep your eye on and someone to know.

Whose idea was the Society? Who started it and why?

It was originally started by my fellow Stark students, Robert Wei and Lior Chefetz (who currently runs the website and database) as a network for people with China knowledge, in order to fill the gap in terms of information and knowledge about how to make films, whether co-production or otherwise, and how to service productions in China.

The Hollywood aspect of it is really a name for everything outside of China, waiguo. The website is there as an online searchable database for members looking to crew-up or find people with skills you’re looking for. Let’s say you’re trying to get a project of the ground and you want to find a producer, you can scroll through that and see if there’s anybody who fits the bill. It was meant as an accessible resource for people wanting to get into China or for people in China wanting to collaborate with people outside China.

What does it take to become a member and what’s in the database for members only?

It’s absolutely free. Membership is through an application online. We screen to make sure that applicants are serious about working in China. We get a lot of students and budding filmmakers. Once you’re approved for membership you can access the database.

Where are the bulk of your members and what’s their demographic?

The membership is fairly divided between the U.S. and China. We do have some members in Europe and Australia, but the membership is probably 70 percent in the U.S. We haven’t yet drilled down into how many men or women we have.

Tell me about the founders Robert Wei and Lior Chefetz.

Robert went to China to work at the China Film Group. He was a founding member in 2012, but has little connection with the day-to-day running of the Society anymore. Lior Chefetz, also from USC, was a co-founder and still maintains the website and database. Lior also had a film at the Shanghai International Film Festival a few years back and has a few projects he’s developing he’s hoping to co-produce with China. Jess Conoplia joined in 2013 to make sure that events ran smoothly, and added mailing lists and e-blasts and liasing with our events partners—until last week, she’s been my co-Executive Director, but she just stepped down.

When did you get involved and what moved you to join?

I got involved in August of 2016. I’d been going to the events for a long time. They were very worthwhile. It was nice to have a regular meet-and-greet for China people just to catch up and talk projects and hear what’s going on through the grapevine.

Unlike a great number of people who become interested in China, you’d lived in China for a long time and speak the language.

It’s always been really interesting to learn what people are most curious about and what they find most convoluted or mysterious about China. I have a certain amount of on-the-ground experience, which I hope people will find useful and informative. I also found it really useful to meet a lot of the people here whom I might not actually get to know if I were purely based over in Beijing.

Who’s drawn to the Society, and what is the biggest perceived stumbling block to working in China today?

It’s quite an interesting mix of people. We’ve got some with quite a lot of experience, either in China or outside, execs or experienced producers. Then, on the other hand, we have very indie producers and students who joined because they want to flesh out their contacts and find out how to get things done in China. In terms of what brings them to China, well, there’s the whole, “Hey I hear there’s a bunch of money in China and it grows on trees and this might be the door to that garden…” Then you’ve got other people who are in it a little bit more for the long game, and just want to keep their finger on the pulse by coming to mixers every month or two to ask people, “Hey, what are you working on?” or “I need such-and-such for productions there.”

Does the Society have other accomplished members like you, who already have produced films in China? Or is the group largely still at the low end of the learning curve?

A lot of people have done or are doing stuff in China. Janet Yang, for instance, is a regular attendee, as well as being one of our advisors. And then there are some people who come along who are working not in film, but in TV. A few members are doing reality TV have a background working with China Central Television, or other Chinese broadcasters. There are not as many people yet working in the web or in new media, which I find fascinating, because it’s exploding and there’s such demand for content.

Finally, there are people like Bruce Hendricks, who did the Pirates of the Caribbean series and worked as a production manager on a lot of Disney projects and has worked a bit in China as well, and is trying to keep a finger on the pulse in there. A lot of people are looking for connections to possible collaborators and information about how to produce in China.

What about the Chinese members? Do they have the same resources? Is the entire site bilingual, even the database, behind the members’ login?

The database is not bilingual. We try to keep the main pages bilingual.

Aren’t we at the point when anybody coming from the Chinese side is surely bilingual?

You’re spot-on on that one.

Have you observed any change among your Western members in their familiarity with or even fluency in the Chinese language?

I think they’re learning a bit of the language. I’m not sure I’m seeing full fluency. There’s a big input from Chinese people who are coming over and graduating from USC and NYU, who have both languages. They become the touchpoints for a lot of the people who need help in China. These people are quickly in demand. There are fewer people older than 35 who are learning Chinese.

Are the bilingual Chinese who graduate from U.S. film schools changing the pace and efficiency of business between Hollywood and China?

You can have Chinese coming to school here and they may have the language, but there’s still a cultural gap and an experience gap. Somebody who’s 25 and graduated from USC or NYU, and who now has an education in film and a certain amount of efficiency in both English and Chinese doesn’t know the film industry, hasn’t worked in it, hasn’t been backstabbed. These graduates are not wearing the scars somebody older would have that might help them push something forward.

Do the Society’s mixers happen in China, too, or just in L.A.?

One of the original goals that we’re still working on is to have a Beijing chapter that runs as many events as we have in L.A. The China Hollywood Society has partnered with the Beijing Screenwriters Group to do an event and mixers during the Beijing International Film Festival. We’d like to start organizing regular events where attendees can come away with practical advice and knowledge.

What are the differences in what’s in-demand on either side of the Pacific? I imagine that folks in Hollywood are looking for Chinese money while folks in China are looking for Hollywood scripts.

Here at the mixers in L.A., there’s a lot of looking for money. In China, the Society is still attended a lot by independent filmmakers and screenwriters, so financing is still one of the heaviest draws at mixers in either market. The people who are looking for scripts in China are the indie-to-middle producers and production companies, and we haven’t had enough mixers in China yet to really draw on that pool. The Society in China started as a group of screenwriters and indie producers and is now starting to widen its circles to encompass people in the mainstream.

Do the mixers invite veterans to come talk with the group?

Right now the mixers are literally just getting people together for drinks to get to know one another and learn what people are doing. It’s about making connections and hopefully giving people a sense that they’re getting something out of it.

You’re about to launch your second film at TriBeCa and you had a debut film widely distributed on China’s streaming platforms. Having lived in China for so long and speaking the language, you have a leg up on many Society members. Do you feel you can still learn from the group?

What’s important is to take the pulse of everybody in terms of what projects are going on: where are they getting their financing? Is that succeeding? Who’s behind it? What are these companies after and what are they making? The Society gives me the opportunity to talk to people I might not otherwise meet, about work I might not normally hear about except through the trades, or even only once it got made.

Personally, I work on indie films that play the festival circuit and get wide online distribution in China, but listening to studio and mid-level people gathered at the Society it’s clear that everybody wants to make massive films—which is not what I make. This is fascinating to me. Everyone seems intent on making a Great Wall-type film, with a $200 million budget, which may or may not make its money back, but everybody still seems very intent on making that kind of film. It’s fascinating to see what China and its film industry represent to people, and what people feel like they want to get out of it.

Do you think so many people are still intent on making another The Great Wall, especially after Jimmy Kimmel mocked Matt Damon in the opening moments of the Oscar ceremonies for joining a Chinese “pony tail movie” that lost $80 million?

Of course The Great Wall was held up as an example before it came out. But everybody still wants to go down that path—the lesson of The Great Wall seems to be a slight shift into doing it for a single market, the China Market or the Western market, but most people I speak to are still saying that they’re going to make a film that’s going to be a blockbuster in China and a blockbuster here.

What’s more common: making movies that aim to span the Pacific or making movies that are again trying first to please their home market in hopes of then expanding overseas?

I see both. In the case of the studios, some are going into TV and also making films purely for the China market, but I also meet a lot of people who still want to make films that are going to be a great success here and a great success there. Not that it’s not going to happen—there’s a track record and a history that shows it’s not very likely, especially when you’re talking about a lot of money at a very high price point.

Are you optimistic about the potential to make movies with Chinese partners?

It’s a many-layered question, because it depends on what type of films. There are definitely plenty of opportunities. I’m currently writing for a company that wants to do a TV series. It’s not a co-production, but it’s still working with Chinese screenwriters and producers. In this realm, I’m very optimistic, because there’s a desire to work together. It’s just about figuring out what the capacity is and working with everybody’s background and what they want to get out of the project.

The web is really exciting. It’s tiny, tiny money, but it’s a nice place to get acquainted with the work and earn something, which I know is not where a lot of the producers want to play, but I think it’s a good introduction. I’m a more cautious about big budget productions and how hard they are for people because as soon as you’re making something very expensive with no guarantee of return, well, that’s when all of your cultural and language problems are going to be a little more stressed.

With Beijing’s restrictions on capital flight, is there less money coming from China, and are there more strings attached?

It’s definitely gotten harder to get money out, but crucially, it also depends on where you’re going to shoot. If everything’s going to be in China, maybe it’s not as difficult. Money has always got strings attached. That’s just one problem on a long list when you’re making a film with China. You’ve got the first hurdles of language and storytelling and then where you’re going to shoot and how you’re setting up your workflow. As far as what comes attached to the money, there are many investors who don’t know anything about the movie business, maybe more than you get here. But they still want to be involved in the creative process, and that’s a hard act to do especially if you still want to have a film that you can sell at the end.

You definitely have the Chinese who are interested in the glamor of the business. And others who just want to get their money out of China, which may be a bit harder for them right now. You also have the people who really want to become producers. They have the money, but no experience, but this is how they’re going to get into the game and get involved.

Why would somebody wishing to move their money out of China wish to invest in a movie over, say, real estate or tech?

I don’t know much about those other industries, but in film, budgets can be quite malleable. You can explain a lot of expenses in film, especially for talent. Just like you can’t put an easy price on a film, it’s hard to price talent. It’s easier to say “We have to pay $3 million to this actress,” even if you could get somebody else with the same talent for $1 million.

Are there any rules that you ask your members to abide?

No, it’s free and easy now, but as we’re planning on introducing a membership fee, that’ll probably come with its set of rules about what constitutes membership and are there different levels of membership.