Popular Indian actor Salman Khan does a scene with child actress Harshaali Malhotra, in “Bajrangi Bhaijaan,” a 2015 Bollywood film that was released in China on March 2. The crowd-pleaser has surpassed big ticket Hollywood flicks like “Black Panther” and the Oscar- winning “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” at the Chinese box office. Photo: IC

Asian rivals India and China have started a new romance on the silver screen.

After the run-away success of the sports biopic “Dangal,” or “Let’s Wrestle Dad!,” last year, Chinese audiences and film distributors have embraced Bollywood’s two-hour, song-and-dance filled offerings with a renewed relish.

So, what’s fueling this budding love between India — the world’s largest film producer that churns out about 2,000 movies per year — and China, which is quickly overtaking the U.S. to become the biggest box office in the world?

For many older Chinese, it is nostalgia. For the young, Bollywood is a breath of fresh air, different from the Hollywood or Japanese and Korean staples they have grown up with.

Wang Yifu, 68, recalls how he grew up watching popular Indian cinema in the late 1970s, when China finally allowed foreign productions after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

“The first movie I watched was “Awaara,” or “The Tramp,” in 1979. It was the first foreign film I watched, and I still remember the songs,” the retired real estate agent said.

“When I think about Indian films, three things come into mind. First, many people from my parents’ generation are very fond of them. They bring up some of the songs and famous quotes even today. The films are usually full of original music and great choreography and the stories are dynamic with colorful characters,” said Xiao Ou, a graduate student from Tsinghua University.

After a few years of success in the early 80s, Indian movies disappeared from Chinese cinemas, partly because Indian producers were more focused on markets in Africa, the Middle East and U.K., where there is a larger Indian diaspora, but also because the waxing and waning political ties between the two nations made it harder to do business.

A smattering of Indian films have had limited release in China since the turn of the century, but many have gone unnoticed.

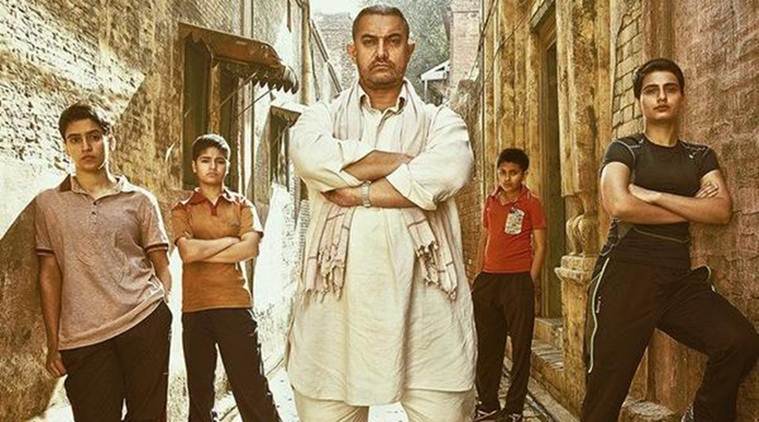

Until last year, Bollywood films remained an afterthought for many Chinese moviegoers. That’s why both film distributors and critics were shocked when a gritty, low-budget Indian film crushed the sequel to the space fantasy “Guardians of the Galaxy” at the box office last summer. “Dangal,” based on a real-life story of a father, who fights gender stereotypes and corrupt sports officials to pave the way for his two daughters to become international wrestling champions, went on to become China’s highest-grossing non-Hollywood foreign movie of all time, earning $190 million.

A poster for the Indian film “Dangal,” starring Amir Khan (center), which became China’s highest-grossing non-Hollywood foreign movie last year. Khan has had a string of successes in China, with his latest film “Secret Superstar” beating Hollywood blockbuster “Star Wars: Last Jedi” in terms of ticket sales in January. Photo: IC

And this opened the floodgates for Indian cinema to return to the Chinese mainland after a two-decade hiatus. The next project by Amir Khan, the actor and producer of “Dangal,” sold more tickets than the Hollywood blockbuster “Star Wars: Last Jedi” in January.

The film, “Secret Superstar,” about a young teenager in a burka who embarks on a secret singing career to save her mother from an abusive marriage, raked in $90 million at the Chinese box office in its first 17 days. That was more than four times the film’s $20.3 million ticket sales in the rest of the world, excluding India.

“Many of the social issues tackled in Indian films resonate with Chinese audiences because there is a similar reality in Chinese society,” said Tan Zheng, a film critic at the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles. “Indian films come across as more authentic and relatable.”

Secret Superstar also became one of the few Indian movies to sign a revenue-sharing agreement with Chinese distributors. Prior to that, filmmakers sold rights to domestic distributors for a flat fee.

The new business model with more profit potential and the fact that India has only half the movie screens compared with China’s 41,000 cinemas, has put China at the top of the list of target markets for Indian producers.

But, China also presents several challenges for Bollywood filmmakers. The Chinese government rules limit the number of foreign films allowed to enter the country each year to protect the domestic film industry, although imported films accounted for nearly half of all earnings at the Chinese box office in 2017. Hollywood films have traditionally taken up 90% of this quota, but after an Indo-Chinese bilateral agreement in 2014, Indian movies have been assigned a quota of up to five films per year.

Then there is the battle with censors. Foreign films have to meet certain criteria with regard to good content, cultural appropriateness, etc. But, Indian filmmakers who aren’t afraid to take a stab at miscarriages of justice, police brutality or corruption in the military may find that such topics don’t go down that well with Chinese censors.

There is also the perennial problem of unpredictable relations between the two nations. For much of last summer, India and China were locked in a border standoff over a remote mountain pass in the Himalayas. In recent years, public perception in China and India here has also largely been shaped by Chinese state media, which tend to highlight negative stories.

But, despite these barriers, Chinese audiences are lapping up Hindi films, and even grandmothers have started jiving to catchy Indian tunes while dancing in public squares.

The record-breaking runs of “Dangal” and “Secret Superstar” in China are largely due to the reputation of 52-year-old actor and filmmaker Amir Khan, who first made inroads into China in 2002 with his Oscar-nominated period film “Lagaan.” The film set during the British colonial period, tells the story of a rag-tag group of farmers who try to beat the English at their own game — cricket — so that they don’t have to pay crippling taxes. “Lagaan” became the first Indian film to be released nationwide in China, and other Amir Khan hits have continued to serenade Chinese audiences.

This includes the 2009 flick “Three Idiots,” a tongue-in-cheek take on India’s high-pressure education system, which promotes rote learning instead of critical thinking. “Three Idiots” remains one of the most highly-acclaimed films in China, ranking 12th of the 250 best-loved movies according to users of Douban, a popular Chinese film review website. That is despite the fact that the film never made it to Chinese cinemas. Viewers knew Khan through bootlegged DVDs or pirated downloads of his previous work.

“The name Amir Khan itself is like a golden pass. If he is in a film, I’m watching it,” a fan under the online moniker “Mr.Mao” wrote on Duoban.

Bollywood’s star power, low production costs and tear-jerking plots that tackle heavyweight issues, albeit wrapped in song and dance, have finally attracted Chinese film distributors looking for fresh offerings. And they are so hungry for content that they are even willing to distribute films released several years ago.

The 2015 film “Bajrangi Bhaijaan,” featuring the other big Khan in Bollywood, Salman Khan, opened in 8,000 cinemas across China on March 2. The dark comedy, about a man who makes a perilous journey across the India-Pakistan border in search of the parents of a lost 6-year-old, has again proven to be a box office hit, earning $2.8 million on its first day.

Chinese distributors have been careful about cherry-picking high-quality productions that address issues shared by both countries to cultivate this image of Bollywood as cinema with a conscience. And some say the success of Hindi-language films may pave the way for movies made in other Indian languages to enter China.

“It’s important to remember that Indian cinema is not just Bollywood. The country makes films in more than 20 languages and some of the regional cinema hubs are as powerful as the one in Mumbai,” said Gu Wancheng, a partner at Peacock Mountain Pictures, one of the production companies behind “Secret Superstar.” “This diversity offers more choices for both viewers and distributors and might help Indian films stand apart from ones imported from other places.”

-This article originally appeared on Caixin Global.