Hollywood Made in China is an elegant account of Hollywood’s evolving engagements in China’s commercial film environment.

In six concise chapters, Aynne Kokas details the myriad flows of policy, investment, deployment, and rewards of Sino-US media co-productions. Her aim is mostly large-scale entertainment schemes, including contemporary blockbusters, theme parks, and studio co-ventures. Because China is now becoming the world’s largest film market, Hollywood is courting Chinese executives and regulators, the better to ensure access to viewers and returns for American pictures. The objective is market access, in return for which Hollywood players are willing to cede control, a tradeoff the author calls “transformative” (33). This is a transaction not available to Silicon Valley (e.g., Google, Facebook, Netflix), and despite frustrations of piracy and capricious regulations, Hollywood may well count itself fortunate. In any case, Kokas demonstrates that the Sino-US co-production enterprise is a work in progress, always in a state of renegotiation and revision, as she aptly puts it: “The Hollywood dream factory and the Chinese Dream work together, while mired in a state of perpetual negotiation” (20). A combination of Hollywood “thirst” for ever-larger markets (old) and China’s “cultural trade deficit” (new) brings potential synergies and symbiosis (2-3). It also brings evolving forms of contention and conflict (13). With every new co-production, new standards and practices appear in the playbook. Aynne Kokas makes a strong case for the “interaction and variability” (8), the unpredictability inherent in this volatile relation.

Chapter 1 outlines the basic trade policies underlying the relations between China and Hollywood. Kokas exemplifies the ground rules of engagement via two big pictures, Iron Man 3 (dir. Shane Black, 2013) and Transformers 4 (dir. Michael Bay, 2014). With the former, she introduces the notion of “faux-production,” a hedge in the trajectory of co-production. Faux-productions arise when the official co-production agreement is declined, either by Hollywood producers or by PRC film industry officials; they are “essentially partial co-productions” (32), because in the end Iron Man 3 was released officially in China as an import and yet parts of its storyline and product placements were unique to the PRC, distinct from those of the US version. The faux-production label is a deft way to account for departures from the co-production script.

Chapter 2 introduces the all-important concept of “brandscapes,” using Disney and DreamWorks properties to create commercial branded landscapes. “Sino-US media brandscapes are capital-driven, real estate-intensive projects that accelerate the growth of marketing infrastructure in China” (41). They are long term commitments, unlike many co-production deals that may end after a picture is released. Brandscapes are most apparent in Shanghai Disneyland, which opened in June 2016 and is Disney’s largest park outside the US. Unable to operate television stations in China, Disney opened a chain of language schools in 2005, freely incorporating Disney characters and films into its teaching materials for children. For a decade, Disney was able to infiltrate its brandscape into China, via education policy of all things, at a time when Hollywood struggled to enter the tightly controlled media market. Kokas writes, “Disney’s English schools become de facto screening spaces, taking the place of theaters and television screens to distributed Disney products” (50). In the Disney classrooms, these worked as educational materials instead of mere products. And when Disneyland opened in Pudong in 2016, a whole generation of Disney fans was there, primed and waiting.

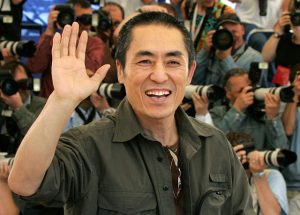

Chapter 3 explores the strategic definitions of co-production policy. The PRC holds much leeway in its handling of co-production protocols, such that foreign capital reception is monitored and regulated by sharp-eyed negotiators, who are quick to make adjustments. In addition to co-productions, there are other types of Sino-US film cooperation, from assisted productions to commissioned productions to buyout films. Kokas’ account of “talent exchanges” is astute. Such pictures feature foreign or “ethnic” actors or actresses in a Hollywood or Chinese film: Li Bingbing in Transformers 4 or Matt Damon in The Great Wall. Damon was pilloried for usurping a role that “belonged” to an Asian face, the same “whitewashing” criticism directed at Scarlett Johanssen in her role as Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell and Tilda Swinton as a Tibetan sage in Doctor Strange. Yet Damon’s role in The Martian (Ridley Scott, 2015) paved the way for his work with Zhang Yimou: it too was ridiculed for its “naked pandering to the PRC market” (78). What annoyed Chinese viewers, however, was the casting of newcomer Tian Jing in The Great Wall because her leading role was, according to online rumors, related to financing, instead of talent. This decision compromised the perceived quality of Zhang’s production as he is known for discovering new actresses with international star potential, such as Gong Li and Zhang Ziyi. Kokas sidesteps this and nimbly moves on to discuss the film profiles of Asian Americans, such as John Cho and Leehom Wang, and connects these to China’s importance in the global film trade. The implication is that cross-pollination is inevitable for roles and casting, given the globalization of films, markets, and stars. Insisting on authenticity is not a sound tactic when judging contemporary blockbusters.

Chapter 4 is about industry forums, the discursive and behavioral norms of co-productions and industry confabs. These take place in both the U.S. and China, and have a range of formality, accessibility, and outcomes. Many happen at the edges of film festivals and other high-profile public events. They include well-known stars, producers, investors, bureaucrats, journalists, and, sometimes, politicians (e.g., ex-senator Christopher Dodd, CEO of MPAA). Dodd’s presence is bound to resonate with officials in China, because the country has been intent on cultivating its creative industries for many years, connecting its soft power ambitions to the notion of “cultural security” (20).

Chapters 5 and 6 detail the activities of film workers on Sino-US co-productions. Kokas chooses the term “compradors” to describe the above-the-line staff, such as writers, directors, stars, and producers. Above-the-line may be seen as the public face of creative deal-making, and so we learn about the decisions made by Ang Lee, James Schamus, and Bill Kong in the 2007 picture Lust, Caution. Here, Kokas may have underestimated the dismay this picture caused in China, not just because of its rough sex but in the sympathetic portrayal of a collaborator, played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai. Lust, Caution is almost reckless in the liberties it takes with the literary source by Eileen Chang and in its worldly sophistication that bleeds into decadence. It bears recalling that Lust, Caution took many in China by surprise, especially officials involved in its approval. It could only be shown in a heavily cut version, and most likely there was a disconnect between the production locale, Shanghai (Zhang Xun, at CFCC), and Beijing, where clearance to show films is issued. In chapter 6, Kokas writes about the experiences of below-the-line workers, such as location scouts, translators, and logistics managers. She makes a fine point when identifying allegorical relations between film-televisual narratives and real-life experiences of those negotiating vicissitudes of intercultural roles and power differences (pp. 34, 148, 158). In the conclusion, Kokas mentions cognate industry practices in the worlds of television, streaming video, and animation.

Kokas’s book is a sympathetic, shrewd account of a difficult relationship. It touches on sensitive matters involving “face,” reputation, and public recognition. Hollywood is a cultural powerhouse of which Americans (with exceptions) are generally proud. Kokas appreciates this, but also respects the control maintained by patient Chinese partners. Her rhetoric is very balanced and evenhanded in the treatment of stories of compromise, haggling, and discreet struggle. There are no clear winners or losers. Except in the preface, where she compares herself to an anthropology field worker, we learn almost nothing about the author’s own experience in the language and culture of China. This is a pity, because she writes with such insight about the policymakers and production choices made by creative professionals. There is fastidiousness in the writing, ensuring a laser focus on stories of cross-cultural policy implementations.

The documentation is very thorough, with some statements in the text carrying six or eight footnotes. This diplomacy is understandable, but it is more productive to bring scholarly sources into the main discussion, even at the risk of digression. Kokas also demonstrates versatility by citing a wide variety of source material from media studies, business administration, marketing, and creative geography. The book also offers various charts, illustrations, a Chinese character glossary, and a filmography.

Overall, Hollywood Made in China is an accessible, intriguing study of an unlikely liaison. It can serve as a template or model for other aspects of Sino-US trade relations. One could also use it as a lively text in international relations, trade policy, or media industry courses. Kokas’ work stands out in Chinese media studies because of its clarity and focus. It cleaves to its central ideas and avoids distraction. Furthermore, the author’s knowledge of film production and film history lends credibility to the account of Sino-US cooperation, and compares well with the best contemporary scholarship, such as the work of Michael Curtin, John T. Caldwell, Michael Keane, and Wendy Su, among others. It is refreshing to read such incisive, disciplined scholarship.

–This article originally appeared on MCLC Resource Center website.