As a researcher at a journalism school, I must admit I am surprised to find myself having to weigh in on the issue of whether Chinese state media outlets should be referring to Chinese citizens as “sissy pants,” but here we are.

Part of the reason for my surprise is that China has a long history of acceptance toward men that might be considered androgynous or effeminate in other cultures, whether in ancient literature and opera, or in today’s TV shows that star “little fresh meat.” Then again, that general acceptance hasn’t prevented the country from experiencing periodic bouts of backlash. The current anxiety and debate over China’s so-called crisis of masculinity, for example, can be traced back to the 1980s — when it emerged as a reaction to the rising status of women and the consequent decline in men’s own relative social standing.

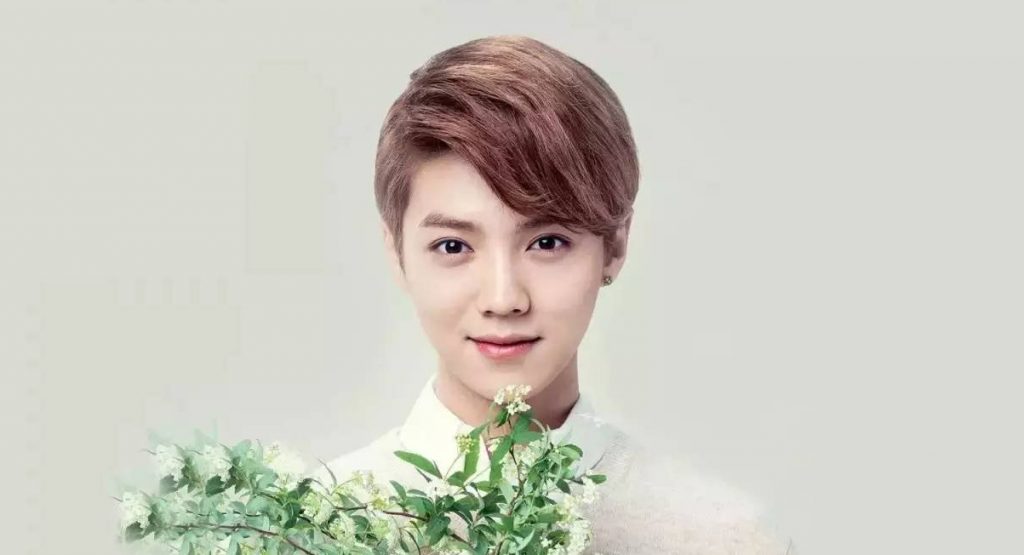

However, this particular long-simmering issue blew up in the aftermath of the annual back-to-school galaprogram, aired on Sept. 1 by state broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) and co-produced by the Ministry of Education. The gala was mandatory to watch for many school-age kids and their parents — who in some cases had to provide photographic proof that they had viewed it together — and the program incensed parents, first by subjecting them to 12 minutes of ads for expensive private tutoring classes, and then by prominently featuring members of the new F4 boy band — seen by some as overly effeminate. Online, many parents criticized the decision to feature the group, calling them poor role models for China’s young boys.

State news agency Xinhua then poured gasoline on the fire when it published a commentary last Thursday lambasting the popularity of young male celebrities who have slender figures and an interest in makeup, calling them “sissy pants” and emblematic of a “sick culture.” Later that day, Party-run news outlet People’s Daily published a rebuttal of Xinhua’s piece, dismissing terms such as “sissy pants” as derogatory, stating that a man’s value should be measured by his character, not his outward appearance.

To understand the nature of this controversy, we must first understand how Chinese have traditionally viewed masculinity. Kam Louie, a professor of Chinese literature at The University of Hong Kong, argues that masculinity in China’s cultural context historically appeared in two main forms: wen and wu — the literary and the martial, respectively. And for most of Chinese history, wen masculinity — that of the scholar, not the warrior — was actually seen as superior to wu, especially when the state was at peace.

To be clear, regardless of whether or not they embodied wen or wu, in those days Chinese men still wielded absolute power over their families and society. Despite this — or perhaps because of it — there was no cultural expectation for men to behave in what would be considered an outwardly macho manner, and warriors were not always lionized over the literati.

In other words, the current backlash against “sissy pants” and inadequately butch men is rooted not in a traditional cultural abhorrence of slender, gentle, and delicately proportioned men — who were the masculine archetype throughout much of Chinese history — but in more modern concerns.

–This article originally appeared on Sixth Tone.