This year’s Tribeca Film Festival boasts almost 100 features and 55 shorts chosen from over 8,700 total submissions. While the majority of titles are from the U.S., an impressive 46 countries are represented.

Many films come from Europe, as might be expected. The United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany and Spain predominate, but films from Scandinavia and South America are also on the schedule.

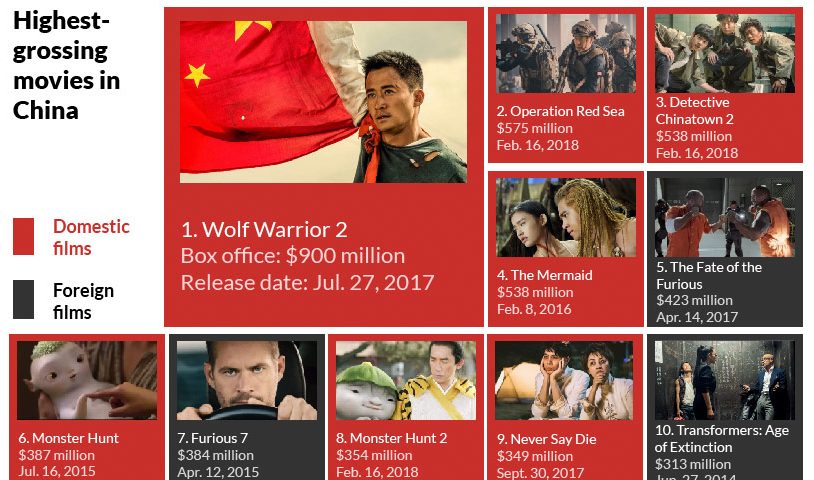

One encouraging trend is the Festival’s focus on Asian films. Variety recently noted that the Chinese theatrical box office is now larger than all of North America’s. And yet Chinese releases, as well as those from Japan, Korean, and the rest of Asia, rarely receive mainstream coverage.

Take Detective Chinatown 2, a broad comedy in the Dumb and Dumber vein. Released over the Chinese New Year, it grossed over a half-billion dollars by April. Even though it was shot in New York City with an American crew, it was largely ignored by the media.

Shawn Yue, one of Detective Chinatown 2’s producers, is a frequent visitor to Tribeca. (This year business kept him in Beijing.) Talking by phone, he noted that language is a serious barrier to Chinese films. American moviegoers are notoriously averse to subtitles. And comedy rarely travels well. But Yue believes a market for Asian films could exist here, even if he has to help build it himself. Festivals like Tribeca are crucial in developing contacts.

Asked why it is so difficult for Asian films to find viewers in the U.S., director Domee Shi said, “I think Asian filmmakers and Asian storytellers have a different way of telling stories. The focus more on slice-of-life moments, everyday details of life. They don’t really follow the Robert McKee three-act structure. They feel more organic.”

Shi and producer Becky Neiman-Cobb were at Tribeca to premiere Bao, a new Pixar short, in a series curated by Whoopi Goldberg. Like the recent Coco and Sanjay’s Super Team, Bao shows Pixar’s commitment to presenting broader, more diversified points-of-view.

“The one way to continue telling unique, different stories is to tap into unique and different storytellers,” Shi said. “At Pixar, some people kept referencing classic Hollywood films like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, all that stuff. But if we want to truly innovate and come up with new ideas, we should look at different sources from all over the world.

“I was born in China but emigrated to Canada when I was two years old. I grew up in Toronto, which is where Bao takes place. It’s loosely inspired by my own experience growing up as a child. I really just wanted to celebrate and pay homage to the Chinatown community I grew up with.”

In Bao, a lonely mother turns to cooking for comfort, then falls alarmingly, distressingly, in love with one of her dumplings. By turns funny, moving and shocking, Bao is above all a story about love. Shi herself worried that the idea might be too dark and strange when she pitched it four years ago. At the time she was working as a story artist on Inside Outfor director Pete Docter. He encouraged her and acted as a mentor throughout the process (and is credited as an executive producer).

Shi agreed that although Bao can appeal to everyone, it is in some ways a deeply personal story filled with region-specific food and details best appreciated by Chinese viewers.

“A lot of non-Asian crew members on the short didn’t understand the toilet paper on the coffee table in the living room,” Shi said. “‘Why is there toilet paper, is that a mistake?’ I was no, no, no, this is very normal in Chinese families. Instead of buying Kleenex and toilet paper, just buy toilet paper and use it for everything.”

Producer Neiman-Cobb pointed to the tin foil used to catch drippings on the stovetop burners as another ethnic touch. She also spoke about how Shi was influenced by Asian filmmakers like Bong Joon Ho and Yasujirô Ozu.

“The way that the film was shot, Domee was all about held cameras and very, very few camera movements,” she said. “That’s an Ozu influence.”

“We watched Good Morning a lot and used that as a reference for how we shot the short,” Shi added. “I also love Tokyo Story, too, and I think I drew a lot of themes from that.”

From the start, Shi wanted to make the short without dialogue or sound effects. “There was a point where there was more there,” Neiman-Cobb said. “But Domee kept stripping them away. We found that every time she did that, the short would get more and more emotional. So even though it’s culturally specific, it’s still so universal, so relatable in its themes of food and family and love, and food bringing families together.”

“It was nerve-wracking,” Shi admitted about watching Bao for the first time with an audience. “I felt like I wasn’t watching the short, I was responding to the audience. But it was cool that they laughed at the right spots and gasped at the right spots.”

Bao will be the opening short for Pixar’s Incredibles 2, an excellent opportunity to broaden the market for Asian-themed movies.

Although technically a U.S. production, the nonfiction short The Girl and the Picturetakes place in Nanjing, the site of infamous atrocities during the Sino–Japanese war. Written and directed by Vanessa Roth, it uses archival footage and present-day interviews to reconstruct a personal account of the Nanjing Massacre that resulted in an estimated 300,000 Chinese deaths.

Roth uses a conversation between 88-year-old Xia Shuqin and her granddaughter Zia Yuan to bring viewers back to 1937 Nanjing. It’s an adroit way to tell the story, one that’s respectful but intimate. Mme. Xia’s account of what happened to her is so awful, so depraved, that it defies belief. And in fact she was accused of faking the story when she brought it to the press several decades later.

But Mme. Xia had proof. John Magee, an Episcopalian priest who ran a missionary school in Nanjing, documented Japanese atrocities with his Bell & Howell home movie camera. He saved many lives in the school’s clinic before returning home in 1940. There his footage was used by the government in documentaries like Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series and later as evidence in war crimes trials.

Remarkably, Mme. Xia and her younger sister appear in the footage. In Roth’s documentary, she returns to the neighborhood where almost all of her family was murdered. She also meets Magee’s grandson, a photographer. Produced by the USC Shoah Foundation, The Girl and the Picture is a quietly powerful argument for preserving history.

Director Stephen Nomura Schible proudly told his Tribeca audience the production crew behind Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda is based in New York. But his documentary, like its subject, transcends borders. Years in the making, it is an intriguing portrait of the renowned musician, composer, actor and activist.

Coda isn’t a typical biography or concert film. Like Sakamoto himself, the documentary stretches boundaries, shifting forward and back through time, weaving archival clips and news footage with scenes of Sakamoto composing, rehearsing, experimenting and traveling. In the Arctic he records water rippling from melting glaciers. (“The purest sound I ever heard,” he tells the camera.) In a New York forest he captures bird and insect songs. Near Fukushima he plays a piano that somehow survived the tsunami that damaged the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Later he stages a concert in the same school that served as an evacuation site during the disaster.

The camera shows Sakamoto practicing Bach on a piano, working with electronic instruments, playing glass bowls and composing on paper and a computer. Illuminating his inspirations and techniques serves to enrich his music, enhancing colors and themes viewers might otherwise miss.

Sakamoto talks about his work as an activist and tells disarming anecdotes about Bernardo Bertolucci and Alejandro G. Iñárritu. Clips from movies like The Last Emperor and The Revenant show how he marries music to imagery.

After the screening he told the Tribeca audience more self-deprecating stories about being fired by Studio Ghibli (“My music was too serious”) and how one of his songs ended up in Call Me By Your Name. A citizen of the world, Sakamoto seems to display the same observant demeanor everywhere. Asked to describe how he composes, he replied, “My way of making music is very close to fishing. I’m always fishing sounds. Fishing and cooking.”

Three other films at the festival were set in Asia. Judith Tong’s quiet, moving short Paper Roof follows two young sisters running away from home. Jeth Heng’s widescreen cinematography frames the children in tight close-ups that bring out their emotions. Other near-abstract shots mimic a child’s point-of-view. Sweet and low-key, Paper Roofis a sketch that suggests Tong has more to offer.

Events have caught up to 9 to 38, a nonfiction short about classical musicians scheduled to perform Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in North Korea. Violinist Hyungjoon Won sacrificed his personal life to arrange the concert. Turned away at the border, they perform instead at a nearby village. Director Catherine Lee seems as surprised as Won that North Korean officials were so intractable.

Written and directed by John Maringouin, Ghostbox Cowboy presents China as a mysterious, unknowable, alien world. Sporting a cowboy hat, Texas businessman Jimmy Van Horn (David Zellner) finds himself befuddled by language, food, business practices, etiquette and even taxis when he flies to China to find backing for a frankly bogus gimmick. Although told with real visual flair, the movie’s narrow point-of-view is disappointing.