- Lawmaker singles out crime thriller Mr Six as inappropriate for kids

- South Korean rating film system a possible model for China

- Censors could no longer hide behind lack of ratings when barring films

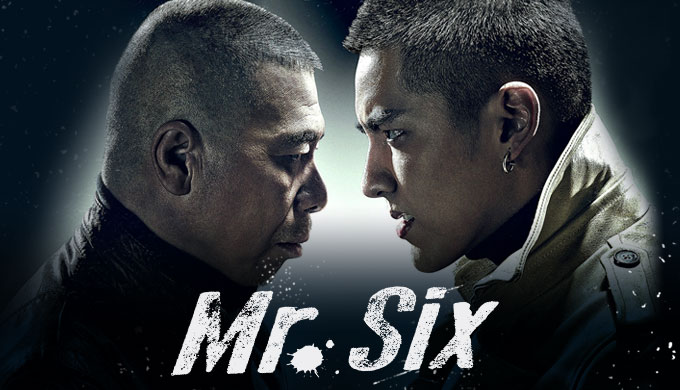

A Still From “Mr. Six”

Pressure mounted this week to introduce a film ratings system to shield children from sex and violence as part of a package of impending laws governing China’s rapidly growing film industry.

A number of delegates and representatives to China’s annual high-level legislative sessions lobbied for ratings as the Chinese government confirmed plans to pass the film laws as a part of the centrally planned government’s 13th Five Year Plan.

China’s longtime lack of a film ratings system, akin to the system used in many Western countries including the United States, has allowed China’s censors to block films from home and abroad from screening without much, if any, explanation.

Zhang Dejiang, Standing Committee chairman of the National People’s Congress (NPC), listed promoting the film industry as one of three priorities to be implemented in the first year of the country’s five-year plan, which runs 2016-2020.

On Tuesday, a day prior to the official start of the annual meetings, delegates met in Beijing to discuss their proposals, including one focused on the need for film ratings.

Because of a lack of ratings—which in the U.S. range from “G” for General Audience through Adults-Only “X”—many Chinese are caught off guard by scary or embarrassing elements in films, Beijing Children’s Legal Aid and Research Center head Tong Lihua, said.

“Many parents have experienced taking their children to watch a movie, and are suddenly confronted with sexually explicit or violent scenes that they are completely unprepared for,” Tong said, Xinhua reported.

Other representatives called for the cutting of more sex scenes, arguing their removal would not hurt the plot of the films or TV shows.

“Are sexually explicit scenes really necessary?” Yang Yanqiu, a Beijing representative at the NPC asked at the meeting. “I heard that Korean TV shows have barely any sex scenes.” she said, adding “I watched some episodes, and it’s true”.

South Korea employs a film ratings system that enables moviegoers to make informed choices independent of government interference, or a lack thereof.

‘It’s urgent and important that China introduces a film ratings system that draws on the experience of other countries,’ Yan Huiying, a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), told Xinhua.

Recent hit film Mr. Six (老炮儿), a crime drama by director Guan Hu, was singled out by Wu Zhengxian, a lawmaker and a director at the Beijing Institute of Education, as an example of a film inappropriate for children.

The title character, an aging Beijing gangster played by renowned director-turned-actor Feng Xiaogang, is a foul-mouthed vigilante who cracks wise about the rich brat street racers who conjure the death of the playboy son of a high-ranking official in a high-speed Ferrari crash in 2012.

Feng, himself a member of CPPCC, has used the platform to complain about censorship in the past. In an impassioned speech at the meetings in 2014, Feng called censorship “a torment” and urged authorities: “Don’t make directors tremble with fear every day like [they’re] walking on thin ice.”

Censorship and free-speech have been an undercurrent at this year’s meetings after outspoken and politically connected real estate mogul Ren Zhiqiang had his Weibo account shut down by authorities after he questioned president Xi Jinping’s call for the media to maintain “absolute loyalty” to the party.

When questioned about Ren’s fate last week, Feng raised a finger to his lips, whispered “Shush,” and walked away, according to the South China Morning Post.

Despite grating on the ear and touching a nerve in some quarters, Mr. Six drew praise from the ruling Communist party’s official graft watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI).

Zhang Heping, head of the state-owned Beijing People’s Art Theatre, said the film’s final scene, in which Feng’s character involves the authorities in his dispute, was a model for citizen cooperation with authorities, according to the Beijing Morning Post.

“This plot point was praised many times by the top CCDI officials,” Zhang said. “Which goes to show the movie not only won over the market, but also displayed sensitivity to the country’s policies.”

Pressure for a film ratings system is coming not just from child-welfare interest groups, but also from the film industry itself. China’s Film Directors Guild called for an overhaul of the entire film industry, including the introduction of a rating system in January 2015.

Theoretically, only films deemed suitable for all ages are released in China, but the opacity of the decision-making process behind the censorship confounds many in the industry—including those in Hollywood.

Stephen Chow’s blockbuster comedy The Mermaid, which is China’s highest-grossing film ever, was open for general admissions on the mainland, but was slapped with an R rating in the U.S. Meanwhile, 20th Century Fox’s Deadpool—now the highest-grossing R-rated movie in U.S. cinematic history—was denied a release in China.

There is still speculation as to whether violent scenes from The Revenant, another 20th Century Fox-distributed film, will be cut before it hits Chinese screens around March 18.

According to the Oscar-winning film’s movie release license, the film’s Chinese version will be 156 minutes long, identical with its American version.

—Additional reporting Zoe Law, Congzhe Zhang