Every day while CFI’s Hollywood readers take in the business of the Chinese film industry, the actual movies can sometimes seem exotic or remote. But in major US cities, mainstream Chinese films are increasingly available: thanks to Wanda’s purchase of AMC and distributors like China Lion, they get American theatrical releases practically simultaneous to their premieres at home. Though they receive virtually no publicity outside the non-Chinese community, these films are more than worth seeking out by anyone serious about engaging the Chinese industry, understanding the Chinese sensibility and familiarizing themselves with China’s talent pool. Periodically, CFI will review and point readers in the direction of noteworthy US releases of contemporary commercial and independent Chinese titles.

Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017), directed by Tsui Hark; written and produced by Stephen Chow.

Distributed by Sony Pictures Releasing, opens in the U.S. February 3, 2017 (cinemas here).

Grade: B-

If you’re going to see one of the two current Chinese films inspired by the adventures of China’s greatest mythological hero, the Monkey King, make it Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back.

Director Tsui Hark and writer-producer Stephen Chow’s fantasy sequel shattered opening day box office records in China (US$52.5 million) at the start of the lunar new year holiday; seeing it in the US will offer a quick snapshot of what draws Chinese audiences out in droves. Assuming you take an interest in that sort of thing and are up for high-spirited adventure and some cross-cultural anthropology, just don’t go to the movies expecting the sort of Hollywood blockbuster that typically sets records in the New York or Los Angeles.

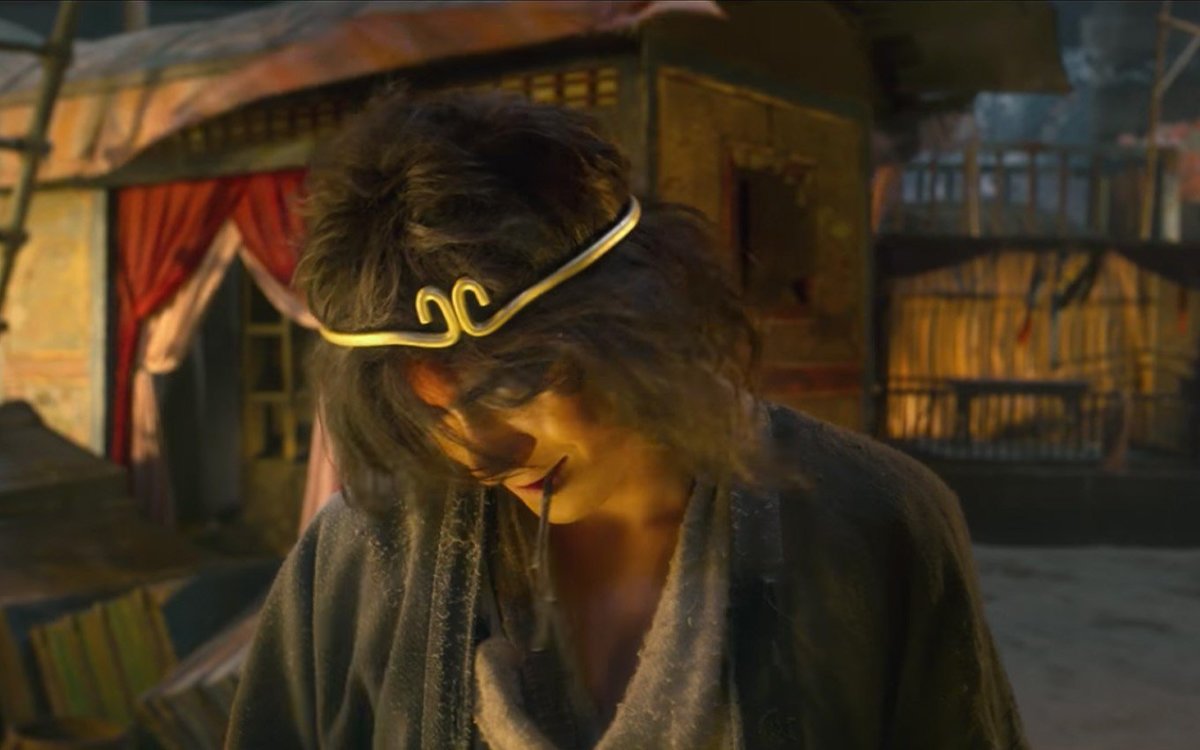

Sure, Journey to the West 2: The Demons Strike Back (JTTW2) features plenty of special effects that propel its heroes, Monk Tang (Kris Wu), Sun Wukong (a.k.a. the Monkey King, played by Lin Gengxin), and their buddies Pigsy (Yang Yiwei) and Sandy (former NBA player Mengke Bateer), through a gauntlet of monsters on their journey to India in search of enlightenment—but the effects are inconsistent, in some scenes spectacular and reminiscent of Terry Gilliam, and then cheap or laughable in others.

These are not the surreal WETA Workshop-like effects of a Lord of the Rings fantasy realm. Sometimes they leave the human talent hanging, forced to cover for their lacking on-screen environment in what ends up being an enjoyable, if accidental, so-bad-it’s-good sort of visual comedy. In one memorable scene, Wu, in monk’s robes, almost succeeds in deploying his pop idol smirk to distract the audience from what’s clearly a run shot against a green screen. Wu hoofs it in slo-mo, away from his alter ego Monkey, across a CGI landscape of gnarled forest. The cartoony, depth-perception-defying jaunt instantly recalled Jimmy Stewart falling out of an upper story in Rear Window in 1954.

To the credit of Wu and his co-stars—including his love interest Felicity (Jelly Lin) and his unrequited admirer The Minister (Yao Chen)—they also show heart. Additionally, for those interested in the Chinese classics, they deliver the clearest interpretation in a while of one tale from the 16th century epic novel for which the film, and many more like it in China, is named. (If you think the Star Wars, Star Trek, and Marvel franchises have sequel fever, you’ve clearly never delved into China’s archive of literally hundreds of Monkey King movies.)

Despite some wild action sequences that deliver Chinese mythology with Alice In Wonderland-level psychedelia—including sexy maidens turned to man-eating spiders, Sandy morphing into the Biggest Fish Ever, and The King (played with brilliant mischief by Bao Bei-er) turning into a nightmarish, petulant demon-child—director Tsui and producer Chow fall short of making a movie that will sprout legs in the West.

American audiences will feel let down if they expect a seamless depiction of an extravagant fantasy world. Chow excels in a kind of kitchen-sink absurdism, juxtaposing ridiculous premises and jokes against one another, and frequently breaking the fourth wall—an approach that mitigates some of the pleasures to be gained from sinking into a large-scale, mythical action-adventure. At the same time, the antics of Monk Tang, Monkey, and company, each of whose strengths complements the others’ weaknesses, possess brio and often inspired silliness that manages to deliver some sincere Buddhist teachings.

So yes, the movie now topping the box office in the PRC, where religion is tightly controlled by its one-party state, has a spiritual message. The message is that we are all subordinate to a greater power called Buddha, and only through surrender to that notion and a practice of cooperation with one’s fellow man (or monkey), may inner peace be attained.

Tsui and Chow, filmmakers formed in the freewheeling crucible of Hong Kong in the 1980s and early 90s, have recently hit their commercial stride in China, spending big budgets and grossing big yuan. Chow’s The Mermaid became the highest-grossing picture of all time in China upon its release at the same time last year.

But as with The Mermaid, American audiences may find the storyline in this latest Monkey King tale too convoluted. Its takeaway—Monkey fiercely battling demons to help his monk master reach enlightenment—sometimes feels akin to a super-loud music video for Beijing’s much-touted campaign to promote Chinese soft power throughout Asia.

As an official co-production that guarantees a greater share of the film’s profits to partners from South Korea, the latest Journey To the West appears to be another attempt at cementing China as the inviolable birthplace of Asia’s most dominant action hero, and a none-too-subtle reminder that said hero, a Chinese monkey, is capable of great things across Asia—from South Korea to India, say. Slapstick subversiveness notwithstanding, it still amounts to a Sinocentric power play that diminishes the appeal of the enterprise. Despite enjoying its great moments of wackiness, my teenage American daughter, who lived the first two-thirds of her life in Beijing speaking Mandarin— came out of a recent screening and said, “They just can’t seem to move past the Monkey King. But they can’t seem to get it right either.”

WHAT DOES THE GRADE MEAN?

Here are some recent & modern-era vintage Chinese and Hong Kong films for comparison

- A+

- PLATFORM (2000, dir Jia Zhangke)

- THE WORLD (2004, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- DRUNKEN MASTER 2 (1994, dir. Lau Kar Leung & Jackie Chan)

- KUNG FU HUSTLE (2004, dir. Stephen Chow)

- A

- LET THE BULLETS FLY (2010, dir Jiang Wen)

- THE MERMAID (2016, dir. Stephen Chow)

- A TOUCH OF SIN (2013, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- STILL LIFE (2006, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (2015, dir. Jia Zhangke)

- LITTLE BIG SOLDIER (2010, dir. Ding Sheng)

- EXTRAORDINARY MISSION (2017, dir. Alan Mak & Anthony Pun)

- MR SIX (2015, dir. Guan Hu)

- A WORLD WITHOUT THIEVES (2004, dir. Feng Xiaogang)

- SUZHOU RIVER (1999, dir. Lou Ye)

- HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS (2004, dir Zhang Yimou)

- RAISE THE RED LANTERN (1991, dir. Zhang Yimou)

- A-

- DUCKWEED (2017, dir. Han Han)

- I BELONGED TO YOU (2016, dir. Zhang Yibai)

- B+

- THE GREAT WALL (2016, dir. Zhang Yimou)

- OLD STONE (2016, dir. Johnny Ma)

- CRAZY STONE (2006, dir. Ning Hao)

- GO, LALA GO (2010, dir. Xu Jinglei)

- B

- KUNG FU YOGA (2017, dir. Stanley Tong)

- RAILROAD TIGERS (2016, dir. Ding Sheng)

- THE WASTED TIMES (2016, dir. Cheng Er)

- CHONGQING HOT POT (2016, dir. Yang Qing)

- MONSTER HUNT (2015, dir. Raman Hui)

- B-

- JOURNEY TO THE WEST: THE DEMONS STRIKE BACK (2017, dir. Tsui Hark)

- SOME LIKE IT HOT (2017, dir. Song Xiaofei & Dong Xu)

- BORN IN CHINA (2016, dir. Lu Chuan)

- D-

- TINY TIMES (2013, dir. Guo Jingming)