Millennials’ devotion to teen idols means big business in China.

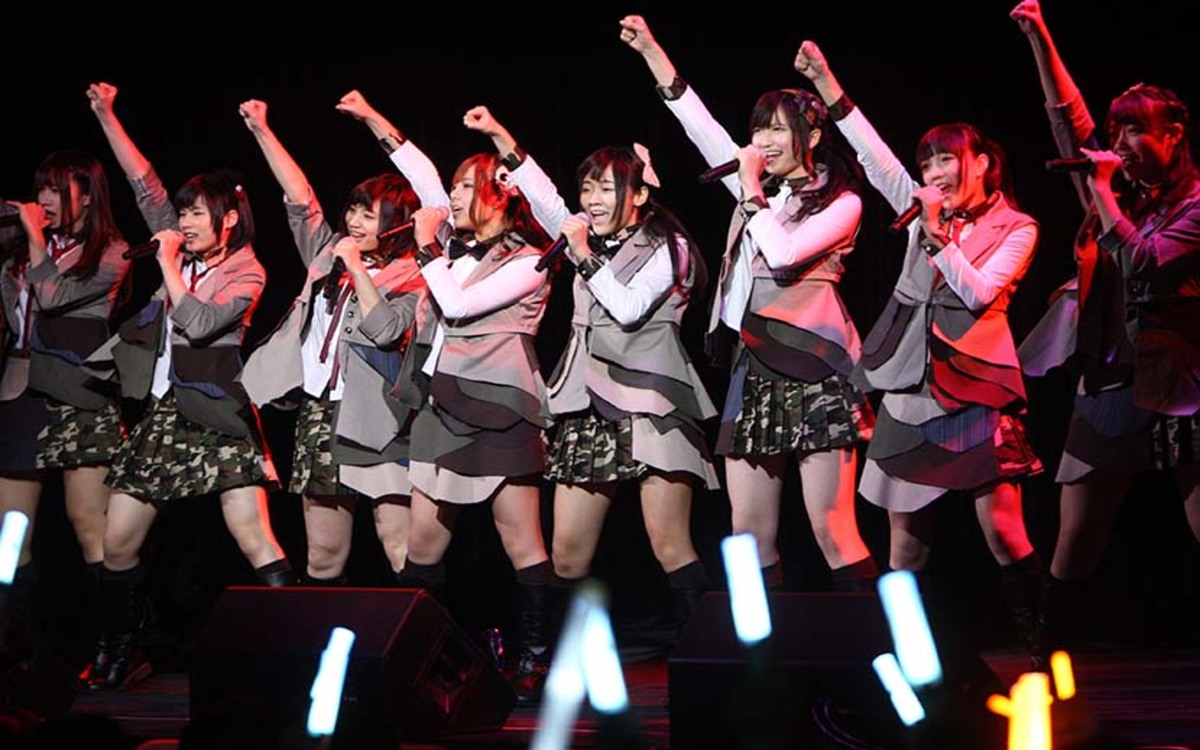

When 15 girls in lace sleeves and bubble skirts took the stage at the Star Dream Theater in Shanghai on a recent Saturday night, the crowd went wild.

For the entire evening, the audience chanted lyrics along with the singers and waved glow sticks in the air with the fervent enthusiasm of die-hard soccer fans.

Such unbridled adulation is usually reserved for superstars, but these pitch-imperfect teen idols are a far cry from the top tiers of talent. Instead, they are yangchengxi, a term that translates as “those who are nurtured.” While pop stars have traditionally sat on high as objects to be admired — from afar — by their audiences, intimacy and proximity with fans is at the heart of these yangchengxi super groups’ appeal. With their spending and voting powers, fans are active agents in the growth of the singers on stage, even determining their eventual success or failure.

Essentially, these girls are amateurs. They belong to the all-female performance group SNH48, founded in Shanghai in 2012 as the sister act to Japan’s AKB48. In fact, much of China’s yangchengxi culture and business model takes cues from Japan and AKB48 producer Yasushi Akimoto. But the Shanghai scene is no small-time copycat. SNH48 — who declined to be interviewed for this story — have launched offshoot groups GNZ48 and BEZ48 in Guangzhou and Beijing, respectively — a move that irked the group’s Japanese counterpart and led to a rupture of the sibling relationship in June of this year.

Despite the split, SHN48 shows continue to copy the Japanese model to a tee. In some ways, yangchengxi performances resemble extended, live versions of televised talent competitions such as American Idol or Britain’s Got Talent, which also showcase contestants’ development over time and allow audiences to select a winner.

What’s different is that very few yangchengxi will ever make a name for themselves beyond the walls of the Star Dream Theater. But that doesn’t matter to their audiences.

The diverse cast of yangchengxi represents a broad range of personalities and interests, meaning there is an idol for every type of fan imaginable. For example, SNH48 member Xu Zixuan, 18, is known for her sense of humor and love of video games. Yi Jia’ai, 21, is known for being kind to her fans. Between songs during a performance, the idols stop to discuss personal topics — some requested by fans — including their favorite films or friendships with other idols.

While widespread fame for individual idols may prove elusive, making a fortune is possible, at least for the companies that have emerged to take advantage of the yangchengxi craze. In the traditional model, an entertainment company usually expects to profit after long-term investment in an artist. But the new trend allows idols to generate profits after minimal preliminary training, no matter how unpolished their performances are.

First, there are the competitive ticket sales. Star Dream Theater has a capacity of just 340 people, including standing-room-only spots that sell for 80 yuan ($12), roughly the price of a movie ticket. Concert tickets must be booked online, and some fans even hire scalpers to nab tickets using sophisticated computer programs.

Then there’s the group’s “48 system” business model, which attaches a price tag to everything from a souvenir mug to an interaction with an idol. If you want to take a photo with your favorite performer, ask for her autograph, or hold her hand during the meet-and-greet sessions, you must purchase a specific ticket for each of these experiences.

Idols are forbidden to contact fans in private, and it’s considered very rude if a fan encounters an idol in the street and asks for a photo with her. “It’s only reasonable that everything must be paid for,” said 36-year-old fan Edmund Huang, an engineer from Shanghai.

A 22-year-old programmer from Hangzhou surnamed Li told Sixth Tone that he bought 200 handshake tickets for one event this year, 72 of which he used on six rounds of handshakes with his idol Xu Zixuan. In the half-year since he became a fan, Li has spent over 20,000 yuan on the idols.

The yangchengxi trend has reportedly caught the attention of big-name investors like media tycoon Li Ruigang’s China Media Capital, as well as Sinovation Ventures, an angel investment fund co-founded by Google’s former China head, Lee Kai-fu. The financial details of those deals were not publicly disclosed.

Key to sustaining the popularity — and, therefore, profitability — of yangchengxi is a dynamic social media world where fans gather to comment, criticize, and encourage their idols. The central appeal of the idols, fans say, is not the young girls’ dazzling performances. Instead, it’s their journey to achieving their dreams.

“Average looks, average figures, average dancing and singing skills — these girls have nothing to be admired except diligence,” said Huang, who has been a fan for two years. When he first started going to the Star Dream Theater, audiences were 90 percent male. Today, women make up about 30 to 40 percent.

Longtime fans compare the earliest performances of China’s yangchengxi scene to a “car crash,” and even today, SNH48’s shows are far from flawless. During one performance, a girl knelt down to tie her shoe in the middle of a dance routine. During another, a girl threw the choreography into disarray when she danced in the direction opposite to the rest of the group.

But such mistakes leave audiences unfazed. On the contrary, for many fans, the fun lies in watching their idols flounder and then improve, encouraged by the audience’s support.

“Here we have ordinary girls who can realize their dreams little by little. It’s very encouraging,” Hu Keyi, a 42-year-old computer engineer, told Sixth Tone outside the theater. “It’s kind of fun to help other people realize their dreams.”

“They know it’s very hard to become top performers in the group, but they are still willing to sacrifice their youth for their dreams and for their fans,” said 20-year-old college student Wang Mengting, who became a yangchengxi fan three years ago. “Their efforts can influence fans, making us feel that we should work harder and take life more seriously. It’s like they’re passing on positive energy,” she added.

In the end, it’s the fans who decide the fates of their idols. The process works like this: Performers are divided into five teams of about 20 members each. Of these, only 16 get to go on stage, selected by audience members whose entry tickets come with a vote that can be cast for an idol performing in that night’s show.

The results decide the idols’ positions on stage: whether they’ll lead the dances or be banished to the periphery. Voting also influences the income they can earn from the shows, and an annual general election further decides the allocation of SNH48’s resources for the next year — who gets featured in magazine ads, who shoots television commercials, and who gets to appear on reality shows.

The fate-deciding general election every summer is the time for fans to turn out their pockets. Besides the standard album, there is also the “supporting album,” which comes with 48 votes and can be purchased for 1,680 yuan, and the “digital album,” which comes with just one-tenth of a vote and sells for 5 yuan.

Each idol has her own fan support group tasked with raising funds for the election. According to the engineer Huang, fans who contribute the most money are called “daddies” by other fans. This year, a fan had to spend at least 160,000 yuan on voting to qualify as a daddy.

The 48 finalists in this year’s general election received over 1.75 million total votes, up by more than 254 percent from last year. The total revenue as of election day, including souvenir sales, surpassed 100 million yuan, according to a report by the 21st Century Business Herald.

Huang said he spends 10,000 to 20,000 yuan a year on yangchengxi, with half of that going toward theater tickets and scalpers, and the other half going toward voting. For comparison, China’s per-capita GDP last year was 52,000 yuan, while Shanghai’s was 103,100 yuan.

“I know my votes don’t add up to much,” said Huang. “They are purely gestures of encouragement for the people I like.”

— This article originally appeared on Sixth Tone.