Welcome to the eighth installment in a 10-part series of practical tips that will make up the CFI Guide to Film Production in China. Publishing each Friday from now until just before the annual U.S. China Film Summit and the American Film Market in Los Angeles in early November, the CFI Guide is built upon wide-ranging research and reporting checked against specific case studies and available official documentation. It is for writers and producers, directors, actors, and members of the film marketing and distribution chain who believe that working with China is a part of their future. With Chinese ticket sales up nearly 50 percent in 2015, and likely to surpass U.S. sales inside the next year, it’s clear that this market is too big to be ignored. CFI is here to help you better understand China’s filmmaking process and industry.—Jonathan Landreth, Founding Editor

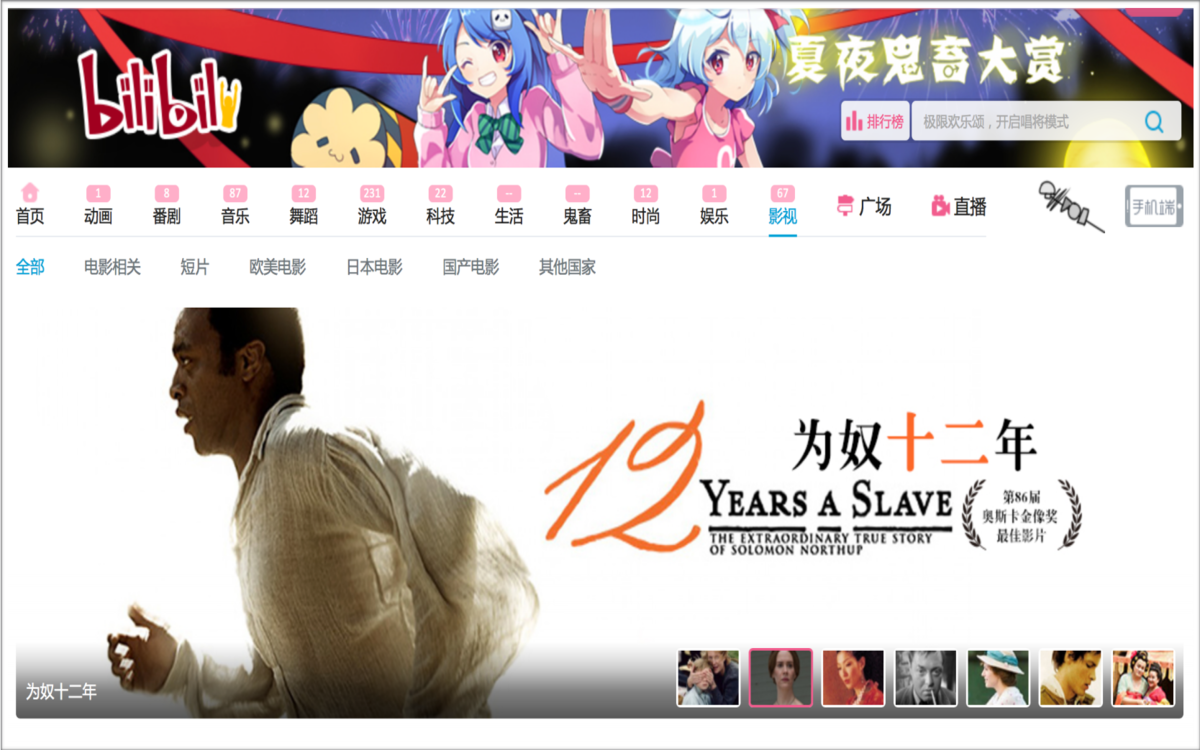

China has had a poor reputation for rampant piracy and disregard of intellectual property (IP) rights for a long time, but both Chinese authorities and private actors have been showing an increased awareness of the need to protect and enforce copyrights. Film piracy is a concern around the world, but cultural attitudes towards intellectual property rights and poor enforcement allowed the problem to mushroom in China, where pirate DVD shops have operated openly for decades and today’s major online video sites got their start as sources for unauthorized viewing of foreign movies and TV shows not readily available. But attitudes have been changing as the realization that there’s money to be made from content has dawned on the industry’s gatekeepers. Piracy is no longer a problem that mostly affects foreign copyright holders, and as Chinese studios develop homegrown content that has proven a success at the box office, the industry wants to ensure that audiences pay for content.

There are three kinds of enforcement available for copyright infringement: administrative, civil, and criminal, with a variety of penalties available under each, including fines, monetary damages, warnings, apologies, loss of business licenses, and prison sentences for the most severe cases. Lawyers in the field see the most success among Chinese companies seeking administrative relief, rather than civil or criminal, against piracy.

The development of higher-quality domestic content by Chinese rights owners has led to greater enforcement of copyright protection for movies, with the China Film Copyright Association leading the charge. It regularly uncovers and reports unauthorized screenings and illegal streams of new films, files administrative actions, and joins studios in taking pirates to court.

In the online realm, there are also clear procedures in place for rights holders to give internet companies notice of copyright infringements in order to get the illegally posted content taken off the internet. Websites and internet storage services must process notices and complaints in a timely manner and remove infringing content or links to it.

Individuals with claims to copyrights have been enforcing their rights as well, most visibly in the series of copyright cases brought by writers against companies and individuals alleged to have plagiarized their work. As the demand for content for movies, television, and the internet has skyrocketed, some writers have taken shortcuts by relying a little too much on the work of others—a trend that has not gone unnoticed by the writers whose work is copied. The recent landmark case in this area involved a Taiwan romance novelist, who successfully sued both the writer and television station behind a China series that bore very close parallels to one of her books. That case resulted in compensation of RMB 5 million ($760,000) and an apology, and, perhaps more importantly, set an example for other writers to go to court to enforce their rights.

Both on paper and in practice, however, the monetary compensation for infringement remains fairly small compared to a country with very strong IP protection such as the United States.

In China, damages awarded do not come close to covering actual losses incurred as a result of piracy. As a result, the threat of having to pay damages for piracy in China is less likely to have the intended deterrent effect. (Sky Canaves)

Read Part 9, “IP is an Industry Obsession.”