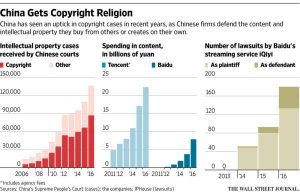

Over the past several years, an increasing amount of creative work has been outsourced to China: everything from special effects for movies to programming for video games to architectural designs for transit-oriented developments.

These creative works are protected by copyright, but not always in a way companies expect. And because so much work in China occurs without a legally enforceable contract, once companies realize their IP portfolio is not nearly as robust as they thought, it’s often too late to do anything about it.

As a general rule, the creator of an original work (e.g., a song, movie, or video game) owns the copyright in that work. This is true in the United States and in China and in most every other country in the world. The main exception to the general rule is for “works for hire,” which are works commissioned and paid for by a third party. But this is not a clear-cut exception: it depends on the facts, and it depends on which country you’re in.

In the United States, a company will own the copyright to a “work for hire” by an employee if the work was made within the scope of that employee’s employment. A company will own the copyright to a “work for hire” by an independent contractor if the work was specially ordered or commissioned for use via a signed agreement that specifically states that the work is a work for hire and such work falls into one of nine statutorily defined categories (including motion pictures, translations, tests, and instructional texts). Many commissioned works (e.g., photography, software, and product design) do not fall into one of the statutory categories, and for those the company will need to have a signed contract that explicitly assigns the copyright. Even in the absence of a signed agreement, the company can argue that it has an implied license, but that’s not a great position to be in.

In China, the presumptions are somewhat different. China’s Copyright Law states that an employee will own the copyright to anything they create during the course of employment, except for engineering designs, product designs, maps, and computer software, and other works created mainly with the employer’s resources. For all other works, the employer essentially has a two-year exclusive license to use the copyrighted material, and thereafter a non-exclusive license. If an employer (a WFOE, say) wants to impose a different requirement on its employees, it needs specific language in a signed contract with the employee that assigns all rights in any “work for hire” to the employer. That contract should be in Chinese and governed by Chinese law, and it should be signed at the beginning of employment.

For “independent contractors” (whether individuals or entities), the contractor will own the copyright unless there is a specific agreement between the parties in which the contractor agrees to assign the copyright to the commissioning entity. And yes, this contract ought to be in Chinese and governed by Chinese law also.

This all sounds reasonably straightforward but a vast number of entities – including huge multinationals – still operate in China without proper agreements with their employees, let alone their “independent contractors.” These companies are essentially operating on the honor system, and sooner or later they’re going to pay by losing valuable rights.

— This article originally appeared on China Law Blog.