Bojack Horseman represents the tip of an alternative entertainment iceberg that younger viewers in China are embracing.

As a zero-sum society where everything must be fought for and contested, China is an exhausting place to live. From birth to death, Chinese live in constant competition with each other, fighting for a better spot in a queue or to have a more impressive CV.

Despite living in a golden age of revival that has brought unprecedented prosperity, some Chinese just can’t find any reason to be happy. Resigned to their lot in life as perennial losers in the game of life, this disenfranchised part of Chinese society have found little reason to live, except to experience more despair and misery.

Previously referred to as diǎosī (屌丝), the outlook of these “losers” is characterized by “funeral (丧 sāng) culture” that sums up their bleak perspective on life. And when it comes to funeral culture, one television show stands above them all: Bojack Horseman.

Now in its third season, Bojack Horseman is an unconventional show, even by Western standards. Revolving around a washed-up sitcom star attempting to regain his lost celebrity status, the animated show follows the titular character as he stumbles in his attempts to find intimacy and acceptance in a world populated by both humans and talking animals.

It doesn’t seem as though such a show would appeal to Chinese audiences who are known for a preference for cuteness, as seen by everything from selfie modification apps to the recent popularization of breeding dogs to look like teddy bears.

And yet, the malaise of cynicism depicted by the show has struck a chord with Chinese audiences – namely, a disenfranchised young generation of Chinese in their 20s and 30s who, like Bojack Horseman, live in an idealized world, but can’t find any reason to be happy. So although the show is a biting satire on Hollywood and the celebrity culture, Chinese viewers have found the dialog in Bojack Horseman to be profound and poignant, quoting it to each other on Weibo in massive numbers.

Yes, Chinese audience can’t get enough of the show described in the Chinese media as “a meticulous picture of despair and self-loathing.”

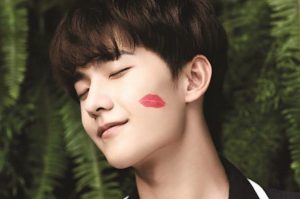

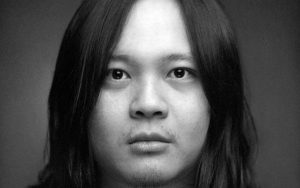

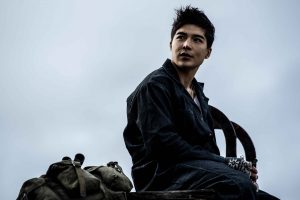

Funeral culture is huge right now in China, so it was only time before this disillusioned group found a spokesperson. Characterized as slackers with no ambition, funeral culture is best represented in China by the “Ge You-leaning” meme (shown below, to the left), the sad Pepe Frog meme (of 4chan fame, middle), and finally, a four-legged salted fish meme (itself based upon a Hong Kong-saying quoted in the film Shaolin Soccer: “In what what are you different from a salted fish if you don’t have a dream?”).

In fact, funeral culture is so big in China that online food retailer Ele.me opened a “funeral tea” café franchise to cater to this demographic.

And it’s not just China. Funeral culture is mirrored across the ocean in Japan where the most popular mascot right now is a lazy fried egg named “Gudetama” who feels that existence is a burden too heavy to bear. Created by the same people who made Hello Kitty, Gudetama is best characterized in a prone position, lacking the will to even stand up.

Unfortunately, whenever anything attracts widespread attention in China, officials will step in to limit its influence, whether it be banning live-streamers on Weibo or detaining a bishop for giving Mass. So, as much as funeral culture in China has to despair for, things just got worse for it.

Just two days after it began streaming on the iQiyi video platform on June 21, Bojack Horseman was pulled by Chinese censors to have its content “altered.”

Western TV shows have been pulled from Chinese distribution before, sometimes for no discernible reason, as when sitcom The Big Bang Theory mysteriously disappeared from the Sohu video streaming platform two years ago.

Bojack Horseman was Netflix’s best chance of cracking the hard-to-crack Chinese market, and this proves to be a huge setback for them. There is no word as to when, or if, Bojack Horseman will return to the Chinese market.

Who knows? Maybe by then, the problem will magically solve itself, and China’s misanthropic younger generation will cheer up. But if things aren’t going to get any better for the second-best diaosi who identify with Bojack Horseman, at the very least they can stop having such a long face.

— This article originally appeared on the Beijinger.