This year’s lineup includes two Chinese language films: The Great Buddha +(2017, Taiwan, Dir. Huang Hsin-yao) and An Elephant Sitting Still (2018, China, Dir. Hu Bo).

For almost 50 years, the New Directors/New Films series has given a platform to promising artists from around the world. Running March 28 through April 8, this joint collaboration between New York’s Museum of Modern Art and The Film Society of Lincoln Center will present 25 features and 10 shorts, many of them premieres.

This year’s opening film, Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. (March 28 & 29) unfolds in an entirely different world. An in-depth look at Maya Arulpragasam, the award-winning artist who uses the stage name M.I.A., the documentary combines concert footage and interviews with Maya’s own video diaries and home movies.

Writers have been asked to hold off on Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., but I’ve been a fan of Maya since her exuberant music-video to Elastica’s “Mad Dog” back in 2000. Despite hits like “Paper Planes” and “Bad Girls,” she has become a polarizing figure in part because people like her were not supposed to have a voice.

A refugee from Sri Lanka who grew up in a housing project, Maya still found a way to bring her music to a worldwide stage. Director Stephen Loveridge’s work is part celebration, part cautionary tale. Maya’s missteps have played out before millions, generating virulent animosity. But her mistakes look to me like honest ones, a result of youth, of misplaced enthusiasm.

Should she pay for speaking out? Is she being punished because she’s that immigrant girl from the projects who won’t just “shut up and make a hit”? Or is she an exacting artist determined to use her platform to further her causes?

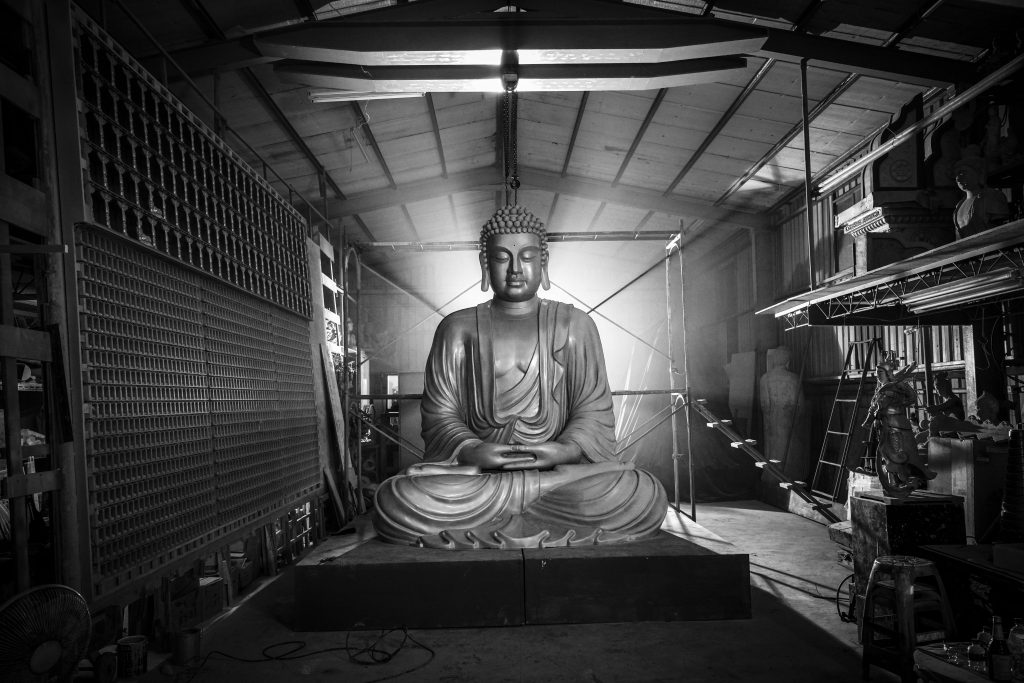

This year’s lineup includes two Chinese language films: The Great Buddha +(2017, Taiwan, Dir. Huang Hsin-yao) and An Elephant Sitting Still (2018, China, Dir. Hu Bo).

Film Journal International‘s David Noh called The Great Buddha+ “compelling due to its mordant wit, authentically observed performances and distinctive cynical/lyrical outlook.” Cheng Cheng Films is handling Huang Hsin-yao’s comedy in the U.S.

It’s unlikely that distributors will be willing to take a chance on An Elephant Sitting Still, the centerpiece of the series. An Elephant Sitting Still (April 1 & 8) screened at this year’s Berlinale, captivating viewers despite its four-hour running time. Written, directed and edited by Hu Bo, it is a technically and creatively astonishing debut with a uniquely enveloping style.

Set in a “third-tier” town in Jingxing (in the Hebei province on mainland China), the film is made up of interlocking stories about residents in and around a blue-collar apartment complex. “A lousy day starts again” is a petty crook’s opening line, and gloom descends from there.

It’s a cold, dark world in which nothing works, the weak are victimized and dreams are crushed. And yet Bo and cinematographer Fan Chao film the characters and settings with infectious energy. Bo’s sense of place and his psychological insight into his characters build enormous suspense. Ten-minute takes that slide from close-ups to three shots to wide panoramas and back draw viewers even deeper into a world that’s both alien and familiar.

Many of the plotlines and characters are built around film noir tropes, but with twists that pull them into the present. A cheating wife, a bullied high-school student, a laborer caught taking bribes, a grifter selling counterfeit bus tickets—they are all depicted with uncanny accuracy and urgency. The more we see them, the more we learn about their motives and backgrounds, the more we care about them.

Bo’s palette may lean grey, his world may seem narrow and depressing, but there’s more life in An Elephant Sitting Still, more honest emotion, than we usually get to see in movies.

Cinematographer Ed Lachman (Far from Heaven, Wonderstruck) saw An Elephant Sitting Still in Berlin, and screened it again in New York. “The way he tells the story, those simple yet elegant tracking shots—it’s a remarkable film,” he says.

La Frances Hui, associate curator of film at MoMA and a member of the ND/NF selection committee, also screened it twice. “This is a film you don’t normally see,” she says. “Maybe once every ten years you find a film with this gravity. His vision is so assured and confident, he knew exactly what he wanted to do.”

Bo brought an early draft of the script (loosely based on one of his short stories) to the FIRST International Film Festival in Xining, China. There he drew the attention of sixth-generation filmmaker Xiaoshuai Wang, who signed on as producer. Conflict between an uncompromising director and a producer anxious to satisfy distributors was perhaps inevitable.

For reasons that remain unclear, Bo committed suicide this past October. Wang gave his rights to the film to Bo’s parents, who oversaw its post-production. (According to Hui’s research, Bo had essentially completed a cut, which only needed some color grading and the final score.)

“It hasn’t shown in China yet,” Hui points out. “It’s not ‘dragon-stamped,’ you don’t see the dragon seal at the beginning, which means it hasn’t gone through Chinese censors. It’s unlikely this will end up in regular theatres in China. This is not the kind of film censors normally approve because of how gloomy it is.”

An Elephant Sitting Still may be equally hard to see in the U.S.. Exposure at New Directors/New Films might convince a distributor to take a chance. That’s one reason why this series remains such an important showcase.

–A version of this article first appeared on Film Journal.