As we’ve seen with South Korea, Hollywood could take the brunt of any Sino-American friction, trade or otherwise.

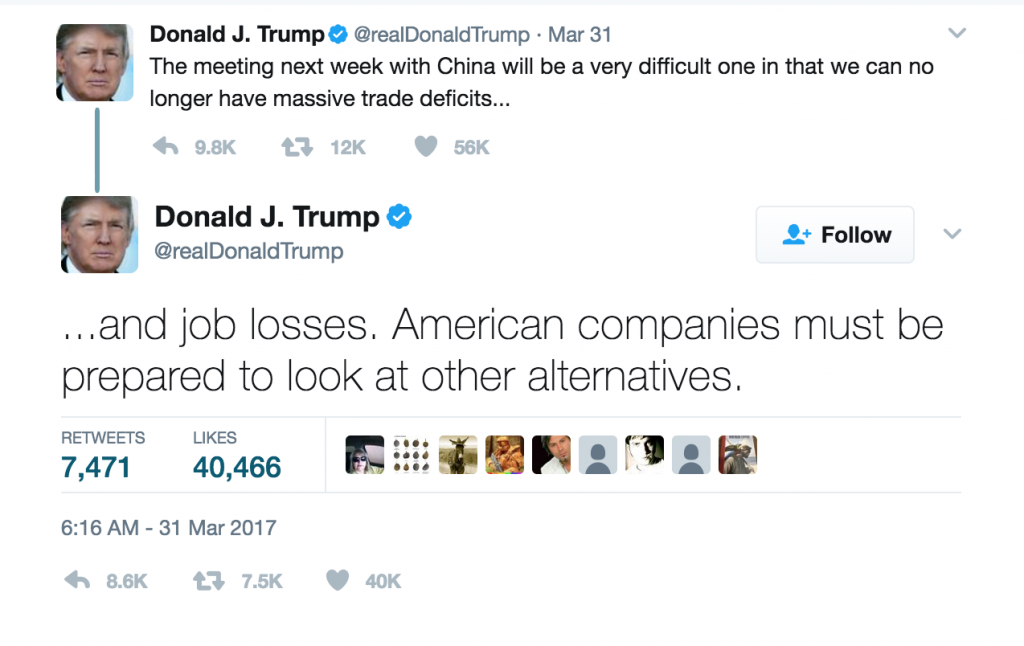

On April 6 and 7, US President Donald J. Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping will convene at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida, the first-ever meeting between the two leaders. Trump has preemptively tweeted that he expects the meeting “to be a very difficult one.” Hollywood should be worried about anything but a positive outcome.

Neither of the two issues likely to be at the center of discussion — specifically, China’s trade deficit with the United States, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), also known as North Korea — will make China particularly happy, especially if Trump presses hard.

On trade, Trump campaigned on taking a hard line with China over both the trade deficit and what he sees as currency manipulation with the RMB. However, while one of Trump’s opening salvos after the election was to telephone Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen — not the PRC’s favorite person — during a phone call with Xi to set the stage for this week’s meeting, he subsequently affirmed the One China policy: that the legitimate Chinese government is the Communist Party of China and the People’s Republic of China, and that Taiwan is a province of that country, not an independent nation.

Trump sees North Korea as a direct military threat to the United States and its Asian allies, Japan and the Republic of Korea (South Korea). North Korea has recently been conducting both ballistic missile and missile engine tests. In response to the North Korea’s capability to deliver nuclear weapons at least to targets in Japan and South Korea, South Korea is deploying the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD),”a United States Army anti-ballistic missile system which is designed to shoot down short, medium, and intermediate range ballistic missiles in their terminal phase using a hit-to-kill approach.”

While Trump wants to see China rein in North Korea and its weapons programs, the THAAD deployment has riled China, primarily because its detection capabilities go far inside Chinese territory, and the PRC is treating it as a sort of Korean missile crisis, an offensive, not defensive, weapons system, and whipping up anti-(South) Korean sentiment. While China has not taken or threatened any military action against South Korea, it has demonstrated its displeasure by enforcing an unspoken ban on most South Korean cultural imports, including wildly popular television dramas, pop music, movies, and live appearances by Korean stars. It has also put the screws to Korean retailers operating in China, for whom China is an important international market, forcing some to close numerous stores due to various violations in their operations.

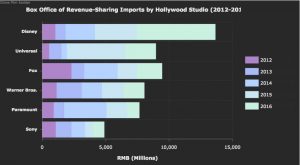

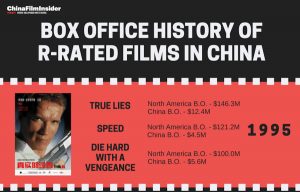

And it is here that Hollywood should worry. Hollywood product is an important revenue generator for China’s film industry via revenue sharing of imported film grosses, but those imports are not guaranteed. At present, China officially permits 34 foreign films that do not qualify as co-productions to be imported under revenue-sharing rules, although 40 were allowed in 2016. American films usually the majority of those slots, due to their popularity and therefore profitability. The total quota is due to be renegotiated this year, although initial indications that those talks would take place in February have come and gone, with no further mention of discussions since then.

From the THAAD example, it’s clear that China is willing to use trade to express displeasure with non-commercial geopolitical issues, and while China’s film industry, coming off a lackluster year in 2016, would take a hit from restrictions or a ban on Hollywood imports, China isn’t inclined to worry too much about the hurt feelings of teenagers and young people who don’t get to see their foreign screen idols — and would just as likely return to downloading movies they want to see from the internet. Similarly, President Trump is no fan of Hollywood, having been roundly criticized by American movie stars including Alec Baldwin, Robert DeNiro, Tom Hanks, and Meryl Streep, and, as such, would be unlikely to put the US entertainment industry’s interests ahead of American industries such as automobiles, energy, or finance.

Trump’s suggestion that “American companies must be prepared to look at other alternatives” may apply more aptly to entertainment than other industries, something that film studios may already be doing in the face of capital outflow restrictions that have scuttled a series of China-Hollywood acquisitions and investments. Unless Trump and Xi emerge from their meetings at Mar-a-Lago all smiles, what appeared to be a deepening relationship between China and Hollywood just six months ago could become even colder and more distant just ahead of the summer blockbuster season.