Up-and-coming directors are eschewing epic documentaries about a changing society in favor of sensitive examinations of the self.

When we think about “independent cinema,” we tend to think of avant-garde filmmakers self-funding their works, writing their own scripts, and directing their own movies — with results that are either critically acclaimed or dismissed as self-indulgent and incomprehensible. But this definition is largely an American import. It originated in the 1940s, when eight major production companies held a monopoly over all movies produced in the United States, and a few pioneering filmmakers challenged the so-called central producer system and went independent.

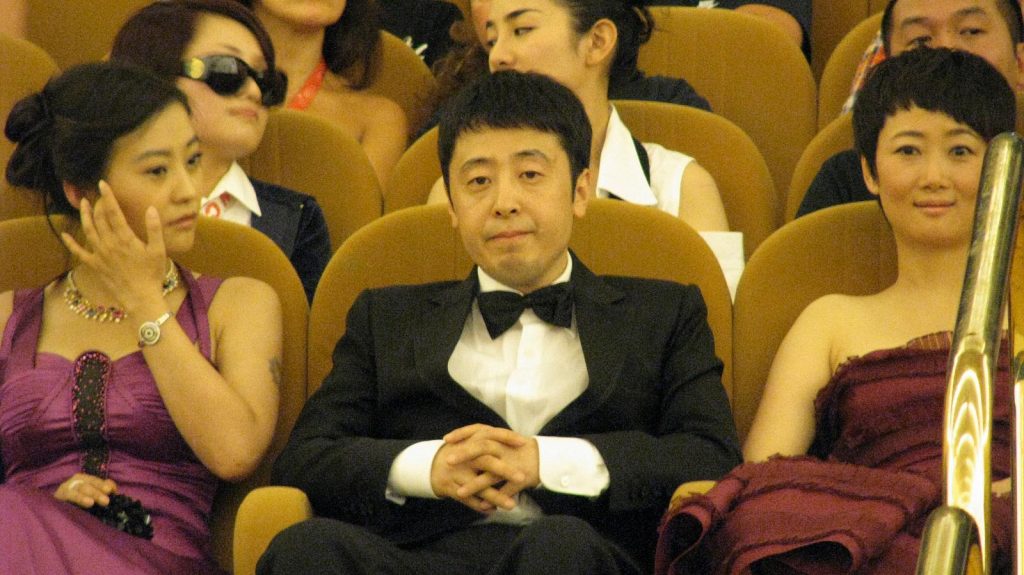

In China, the concept of independent cinema is considerably more complex. When the term fell into common parlance in the 1990s, audiences usually used it to describe films that portrayed the lives of the marginalized. The so-called sixth generation of Chinese directors, who were mainly active toward the end of the 1990s, embody the Chinese notion of independent filmmaking, particularly the early works of Jia Zhangke, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Zhang Yuan.

After the turn of the century, independent moviemakers targeted the well-regarded independent film festivals of Nanjing and Beijing and created wide-ranging, documentary-style films in digital format. Many filmmakers explored social issues like state-sponsored land requisition, environmental protection, education, and urbanization. They largely focused on the people living on the lower rungs of society who rarely appeared in mainstream cinema, like laid-off workers, farmers, city beggars, and criminals undergoing re-education through labor.

Many independent documentaries made crude use of technology — the sound and picture quality fell far below what is expected of today’s movies — and employed a narrative style that was direct to the point of being jarring. Nonetheless, these films still gave a voice to China’s social underclasses and sparked discussions of the issues they faced. They challenged taboos about discussing social conflict, combining incisive storytelling with a melancholy aesthetic.

Taking such a tack were films like Wang Bing’s “Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks,” which described the decline of a factory following China’s market-oriented reforms of the 1980s; Huang Wenhai’s “Dream Walking,” which depicted the rootless lives of artists and poets; and Zhao Liang’s “Return to the Border,” which told the stories of ordinary people petitioning the authorities, hoping for personal redress or policy changes. Since 2010, a new form of independent cinema led by directors born in the 1980s has become a veritable force in China’s film industry. Continue to read the full article here.