Does the Middle Kingdom’s growing use of quality previsualization efforts portend greater VFX-heavy film success to come?

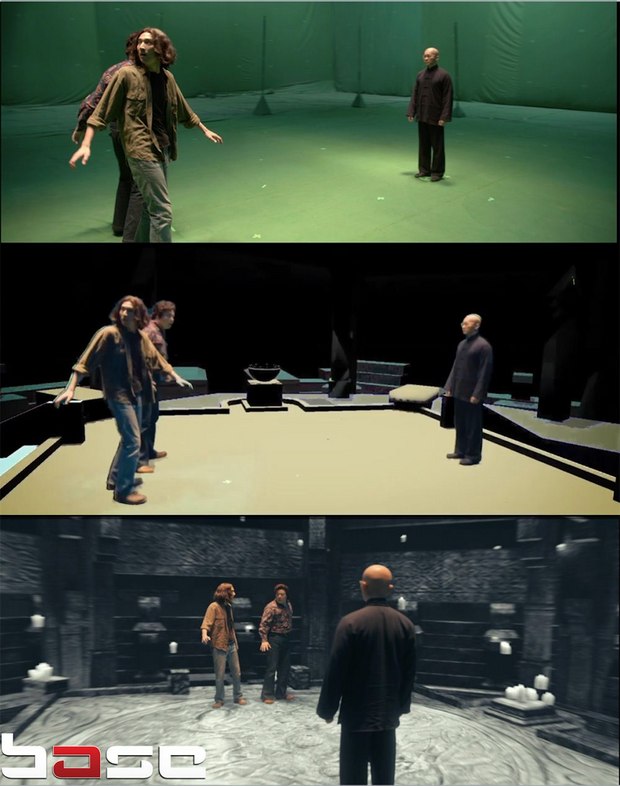

‘Monster Hunt” previs images all courtesy of Base FX.

As one Hollywood visual effects juggernaut after another is rapturously received in China, it is not difficult to understand why the country’s burgeoning film industry would aspire to integrate such technical prowess into their own movies. Whether motivated by passion for the craft, patriotic pride or desire for profit, Chinese studios are eagerly seeking to emulate the visual wonders routinely emerging from top studios in Vancouver, Wellington and London.

As China embarks on this arduous creative quest, much recent talk in local production circles has centred on a set of filmmaking disciplines commonly lumped together and referred to as previs, production techniques now ubiquitous in VFX-heavy Hollywood. On stage at Beijing’s visual media production conference, ICEVE, in 2016, The Third Floor CEO Chris Edwards, declared, “I think [previs] will be a revolution in China, for the betterment of the whole industry.”

Although previs has not yet truly taken hold, there has been a groundswell of early adoption that suggests Edwards is not wrong to predict major changes are coming. Beijing-based Base FX previs supervisor, Gavin Boyle, confirms the trend, noting, “When it comes to previs, China is booming. I’m swamped with work right now. We’re actually pushing work back because there is just not enough time to do it. A lot of my colleagues around Asia and the US are coming here to pick up Chinese work.”

While there have been successful examples of Chinese previs use, like on Monster Hunt and Chronicles of the Ghostly Tribe, whether the rapidity and pervasiveness of its current penetration in China is impactful in the short-term is open for debate.

‘Chronicles of the Ghostly Tribe’ previs images courtesy of Base FX.

***

In Hollywood, CG-based previs came into its own in the production of blockbusters in the early noughties. Its emergence followed an evolutionary process stretching back to storyboards used on Disney Studio films in the late 1920s, through filmed sequences using miniatures for the 1970s Star Wars films, to early CG iterations for Jurassic Park and Mission: Impossible. In China, on the other hand, it is essentially brand new.

The first notable previs appearance in China came in 2013, on the live-action-animation / hybrid movie, Monster Hunt. Primary studio Base FX and client-side vendor ILM decided it would be valuable to help director Raman Hui develop and refine story sequences for what promised to be a challenging, VFX heavy production.

Monster Hunt went on to become the highest-grossing film ever in China and an example for all else to follow. The seeds of the previs revolution had been planted.

But the almost overnight change meant producers had no time to come to grips with these powerful new production tools. Speaking at ICEVE, BangBang Pictures founder John Dietz, a VFX producer and supervisor with more than 20 Chinese film credits, described previs in China as a “catchphrase,” explaining, “Everyone does it, but they do it for the wrong reasons. They just throw somebody in a room and finish it, but they’re not looking at the film. There’s a quality level, and a ‘why-are-we-doing-this?’ question, that not everybody gets here yet.”

Above all, Boyle explains, previs is a tool used in service of storytelling. “We’re trying to figure out certain things that aren’t translated through the script or storyboard, to try to develop the story that really works. That’s where previs shines.” However, so far, decisions to employ previs have too often been made on a financial rather than a creative basis. Those decisions stem from a common belief among investors and producers that movies need spectacular visuals to sell, ergo they must need previs.

Unlike Hollywood, where the evolution of previs was driven by the creative needs of directors, Chinese directors have suddenly found it thrust upon them. It is not only a new tool, but also necessitates a completely new way of working. According to Boyle, prior to 2013, apart from some limited use of static storyboards, directors “never really thought about pre-planning shots. They would basically just show up on set and shoot it. Pre-production in the way that they used to make films was almost non-existent.”

It’s worth noting Boyle has witnessed a mixed reaction from local directors, many of whom, unfamiliar with the technology, “feel that their hands are tied…like previs is controlling their creativity and that their vision is not being executed the way they want it.” It leads some to disengage from the process and limit their interaction with the previs team, or communicate via an intermediary, like a VFX supervisor. Such an approach completely undermines a highly collaborative process like previs.

Others, Boyle says, have begun to realize the benefits of working closely with the previs department, working through shots and conveying their vision. He is encouraged by recent experiences with directors like Ning Hao (Crazy Alien), Guo Fan (Wandering Earth) and Eva Jian (Legends of the Sun and Moon), who have gotten more involved in preplanning and embraced the technology.

Meanwhile, domestic mega hits like The Mermaid and Wolf Warrior II continue to attract investors seeking to cash in on the booming feature film market. The result is what Base FX founder and CEO, Chris Bremble, calls a “rush-rush mentality:” a push for quicker turnarounds and lower production costs, inviting less risk and faster return on investment.

Budgets for the likes of Star Wars: The Force Awakens ($306m), The Avengers ($220m) and Jungle Book ($175m) dwarf those of the average Chinese VFX production, such as Monster Hunt ($30m), League of Gods ($40m) or Wolf Warrior II ($30m). Previs teams in Hollywood will start working on previs at the pitch stage, continuing throughout pre-production, sometimes allocating months to certain sequences alone. In China, teams are sometimes expected to previs whole movies in a few months — Boyle and his team had just three months to previs 900 shots on Monster Hunt.

Tight schedules and what Boyle describes as “ridiculously small” budgets present an inhospitable environment for nurturing a complex creative and technical process like previs.

Moreover, with more than 600 movies in production each year, domestic talent resources are perilously stretched, especially in a highly specialized field like previs. At ICEVE 2017, Beijing-based MORE VFX CTO Yongmeng Wang said, “The talent shortage is the industry’s biggest challenge.”

Yongmeng Wang

Boyle says that previs is a particularly difficult area to recruit for, because, “It’s not just a case of going to a school and hiring a bunch of people from a 3D program. I always look for a good generalist, someone who has a very good eye, who really understands what we’re making…who understand film, from lensing to camera language, editing, how everything is set up and how to work with the director on their vision…That is very, very hard to find here.”

The education system is failing to keep pace with the rapidly growing creative industries. There aren’t enough quality arts universities, and even the best are struggling to train industry standard skills. Previs’ newness to China means there are very few instructors around with hands-on experience in a real production environment.

Starved for artists and under time pressure, many VFX companies can’t or don’t take the time to train young talent. Wang explains that these companies “think artists should produce work immediately after they’ve joined. They don’t give enough time for newcomers to learn. It pushes the best artists away to continue studying or to other industries.”

Lack of supply and rampant demand fosters a counterproductive professional culture. John Dietz notes, “People get taken and pulled from one project to another and they make decisions based on money. Not everyone’s number one focus is on quality. That goes for everybody — directors and DPs. Everyone’s scrambling from one project to the next.”

Money driven decision-making is detrimental for artists aiming to master any one discipline. Furthermore, the strength of the team they leave suffers, as vital project knowledge and experience is lost — the productions these artists jump to risk installing inexperienced talent into senior positions they aren’t yet qualified to hold.

Boyle, however, remains upbeat. His core team, all hand-picked, has been with him for four years, despite receiving offers elsewhere. He finds the best way to develop artists and promote loyalty is providing exposure to high caliber projects and opportunities to learn from experienced professionals. “They want to learn previs and I teach them the proper ways of doing it,” he says. “They also get exposure, not just from working within the studio but from going on location, working in the director’s office, getting exposure to everyone surrounding that production. Ultimately, they find it’s the best for what they want to do.”

Gavin Boyle

Scores of previs studios have emerged to meet the newfound demand, but the novelty of the techniques and the shortfall of training mean many don’t fully understand the service they are selling. “They are looking at pretty pictures,” says Boyle. “They think it’s beautifully rendered storyboards, but you can’t shoot it.”

In a mature industry, natural selection wouldn’t allow such studios to exist for long. But in China, inexperience permeates every stage of the process, including the client-side producers hiring the previs teams. Boyle says with tight budgets, key decision-making criteria is often based on cost rather than quality. “[Client-side producers] think previs is not that important, but the director wants it, so we’ll hire a small studio that will do it practically for free.”

He adds, that ultimately, “it’ll bite them in the butt. The previs won’t be able to provide anything they need on a technical level because it wasn’t set up properly.”

Small budgets mean local productions generally can’t afford to hire the leading global facilities. However, where possible, Dietz tries to make it work, explaining, “When we face the hard problems, we go to the right people. It’ll be a higher cost, but it’s better for solving it.”

To date, he has worked with The Third Floor on previs for half a dozen Chinese movies. He describes an integrated system sharing the workload between his team in China, which does the simpler work, and The Third Floor, which handles “the hard parts of the storytelling, establishing the action tone with camera, choreography, and editing.” He feels it not only benefits the show, but also rubs off on the locals. Dietz adds, “I see people getting much better. There’s just this inherent improvement. They’re being exposed to people who have been doing this for so long. They see a benchmark and they are pushed.”

For most productions, however, working with international studios is a relatively unexplored practice. Besides price concerns, Dietz notes, “Chinese producers are worried that westerners don’t know how filmmaking here ‘works,‘ and that they aren’t used to the business and organizational differences, which are usually based on relationships and more chaotic.”

Wang concurs, adding, “Communication between Chinese is very specific. Relationships are crucial. Foreigners can find that hard to deal with. Coming alone, directly, can easily lead to big problems.”

Producers also worry that western vendors won’t understand Chinese storytelling, both due to language and cultural differences, making it difficult to realize the director’s vision and ultimately connect with the audience. Wang recalls the production of Beyond Time, for which director Ning Hao hired experienced British studio Double Negative, only to encounter problems communicating on set. Hao brought MORE VFX on board to serve as a bridge. “We know what Chinese directors want to express,” says Wang, “and we know how to express their thoughts in industry language. We’ve grown up in this culture so it’s easy for us.”

Despite their reservations, Dietz would like to see local producers strive for better quality production partners, regardless of the challenges that might present. “My experience is that a lot of the Chinese filmmakers don’t exert themselves out to the rest of the world. They assume all these different things,” he says. “Everyone should be more open to finding the best people to solve the problem and trying to figure out ways to make it work.”

Western facilities harbor their own reservations about providing not only previs, but the gamut of VFX production services, on Chinese films, borne out of either negative perception or first-hand experience. The major concerns revolve around Chinese productions lacking a clear vision of what they want, running to the agreed schedule and paying on time.

It might seem that the logical move for foreign companies is to setup a permanent presence in China. To date though, the required time and financial investments, along with a myriad of other challenges, have caused most of the major global players either to tread carefully in their expansion, or stay away entirely. Rather than start from scratch, ILM formed a strategic alliance with Base FX in 2013. The opening of Digital Domain China in 2015 is essentially a renaming and upgrade of Postproduction Office, the established China-based studio that it bought into. MPC arrived officially in 2015, following a partnership with Shanghai Film Group, and focuses exclusively on commercials, while Framestore operates a satellite office in Beijing. At ICEVE 2016, Chris Edwards announced plans to launch The Third Floor in Beijing, although that has yet to materialize. Pixomondo is perhaps the most notable success story. Although its original Shanghai studio closed in 2013, its Beijing facility has established itself as one of the country’s leading VFX production players.

***

The Chinese authorities are naturally assuming a central role in developing the nation’s film industry. In 2016, the Beijing government established the Advanced Innovation Centre For Future Visual Entertainment (AICFVE), an $8m/year initiative charged with mentoring, chaperoning and counseling the development of cutting-edge visual media production technology in China. ICEVE is its showpiece event every Autumn.

Though China tends to be locked on fast-forward, “revolution” is too simplistic a term to describe the film industry’s journey. Rather, it will be an evolution fueled by gradual hands-on experience, exposure and education. Despite natural frustrations, practitioners like Boyle, Wang and Dietz are optimistic. They cite significant improvements in the years since Monster Hunt. Budgets are creeping up, and with an abundance of projects there is no shortage of learning opportunities. With more experience, directors will better understand the value of previs and producers will be able to make better use of limited resources.

“The complications of a growing market need time, quality, focus, and thought,” says Dietz. “But, there is a lot of passion and a lot of people really caring about what they do. If more people in the market can think like that, I think the quality will go up. These kinds of things don’t cost any money. It’s about treating film with the respect it deserves and it’s what we do.”

– This article originally appeared on Animation World Network-AWN.com.